Of the few people that actually like and follow Dream Unlimited, the story has always sort of been that the balance sheet understates the value of the company, and the equity is cheap in relation to this “hidden value”. That was certainly my first thesis.

I have been writing another post on Dream, and it more or less was following the same narrative. Dream owns a bunch of real estate and units of its public subsidiaries, those are worth essentially what the balance sheet says (though I think all three Dream subs are undervalued by the market). However it owns 9100 acres of land that is clearly worth more than it is carried for in the financial statements. See this example of a large land sale earlier this year.

Dream’s sale of Glacier Ridge

Dream also has a few more assets that are worth more than they are listed for, including the Arapahoe Basin ski hill and its development assets in Toronto and Ottawa.

I got stuck a little bit on my writing when I came to valuing the land and condo inventories, which is what has caused the post’s long delay. I don’t find it easy to value those assets, and part of the rationale of the post was to show that even with COVID haircutting values Dream was still cheap. It was doubly tough to first come up with what I thought those assets were actually worth, and then what was fair to discount them.

Finally I gave up. I considered scrapping the whole post. Sawbuckd published something on Dream a while ago, and it is as good as anything I could write. Sure I could write at length about how Vail is valued at 9x EV/EBITDA and Arapahoe Basin would fit Vail’s network nice, ski hills have scarcity value, etc, so Arapahoe Basin could probably be sold for upwards of $100 million, I could come to a roundabout justification that the 9100 acres of land are worth $100,000/share, how the Distillery district is incredible and undervalued, and if you put all the pieces together, nothing below $30 or whatever for the stock makes sense.

I’m not going to do that though.

Not that it all isn’t true, and not that I think it is irrelevant or anything. No, I’m just starting to see that the story is so much simpler.

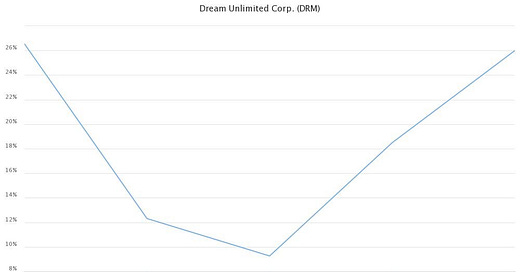

The other day I wanted to test the waters on Dream, to see if maybe I had it wrong, and I found a few charts that I think can tell the story as well as anything.

If I showed you nothing but this graph, you’d probably want a bit more information, but I’d probably tickle your curiosity. Maybe the company is shrinking and the great ROE doesn’t say a whole lot (CI Financial is one example where I’ve hear this criticism).

So Dream has been able to earn very good returns on a growing equity base.

And despite this history, Dream is now as cheap as it has ever been.

I can’t get these facts to jive. The only thing that I can think of is the market is saying that Dream is going to earn a lower return on its equity going forward, which might be true (leverage is lower, and assets will increasingly be on the balance sheet at fair value instead of cost) but the charts above only include the time after oil’s big collapse. If there was ever going to be a time that Dream couldn’t earn adequate returns, it would have been during this time. Since the end of 2014, the only headlines about Alberta real estate have been negative, and yet Dream, which had 70% of its assets in Western Canada in 2013, has managed to earn an average high teens return on equity since oil collapsed.

What would you guess a Western Canada real estate developer earned during this time period?

You see, Dream’s stock price has suffered for the past few years because it was seen as a Western Canada developer. Dream diversified, and now the value of its Toronto and Ottawa assets could be higher than its Prairie assets. The company is likely suffering for that now, with everyone suddenly having the idea that urban real estate has no appeal if more people are working from home. I disagree vehemently with that idea, but from the looks of the REITs that have development land in Toronto, the market doesn’t care what I think.

The market could be saying “Dream can’t earn much by building on that Alberta and Saskatchewan land, because nobody wants to live there. Nor can Dream make money in Toronto since nobody is going to want to live there if they can live in Sudbury for 1/5th the price and work from home, so Dream can’t earn money by building on the Toronto land either”. Preposterous. Dream was able to make money developing out west every year but last year (and last year’s loss was due to a non-cash writedown of Regina land) in possibly the worst environment imaginable. As for Toronto, convincing you that people are going to keep buying and renting real estate in Toronto is beyond the scope of this post, but I’m confident it’s true.

Maybe the combination of Toronto and Alberta being soft markets (I wouldn’t want to argue prices/rents don’t go down near term) means Dream makes a little bit less developing for a while. That ought to be offset by Dream developing more.

Alpine Park is a 650 acre development on the outskirts of Calgary, which will be adjacent to Calgary’s new Ring Road (a new 6/8 lane highway that will reduce the drive from Alpine Park to downtown Calgary to 20 minutes). The project is ~7% of Dream’s western land inventory, sitting on the balance sheet at a pittance of the value that will be realized.

Very rough, and not to scale, showing the Alpine Park development in relation to Ring Road

And not only is downtown accessible from Alpine Park…

This shows Alpine Park (in red) in relation to both the city and some of the most beautiful land in the world

The homes on the west edge of Alpine Park are going to have a hell of a view, and most homes will be just a little over an hour from Banff, not to mention how close the neighbourhood will be to all that other parkland.

I don’t mean to say Alpine Park is some gold mine, though I think people are likely underestimating the value there. More important than the cash Dream can pull out of Alpine Park is simply the fact that Dream is actively pursuing its monetization. Dream bulls will tell you the value of the land is more than it is carried at, but for all intents and purposes that’s a theoretical discussion until value is realized. While the land is just sitting there, the only ways to decide the value of the land is to do something resembling a DCF (troublesome because you’re guessing timelines, costs, and values) or to look at what similar land is selling for and apply some discount to account for the uncertainty of the timing of a sale.

Now that Dream is working to develop the land, the timeline is far more visible. We know that over the next five years, call it seven if you don’t want to trust what the company says, Dream is going develop 800 residential lots and almost 500 apartments units. We know Dream has commitments for its first 200 lots, sales which will happen in the next two years. And we know over the next 15 years Dream is finally going to turn this land, originally purchased in 1997, into cash. If you think of it in purely ROE terms, here’s an asset that was sitting there not earning anything – going up in value but that’s not reflected in earnings – that now will be.

If you’re using a NAV to value Dream, I suppose you could capture how much more valuable this land is now that it is known by the public that it is being developed. I wouldn’t want to be the one doing it though. It needs to be valued differently than just any other land in a “land bank”, and I’m not sure people are doing that. You could do it, take the value of the land on the balance sheet (I would just be guessing what the cost of these specific 650 acres are), then do a model of the timing of cash in and outflows from the land. That’s way above my pay grade, and I don’t think it’s necessary.

I do think there is a reasonably large difference between Dream’s book value and its true net asset value. For instance, CIBC estimates the NAV is $34, and I have no reason to doubt their analyst. But book value is so far above the current share price I think splitting hairs over the NAV is time better spent on another pursuit. Even if you want to spend your time evaluating Dream you’d be better off looking at the quality of Dream’s assets instead of trying to value them. The assets are worth a lot more than Dream’s equity value implies, and they are good assets, which will be in demand in 5 years and 10 years and 20 years, and Dream earns a high return on those assets.

By all means, if you want to do more work than that, go ahead. I think you could be majoring in the minors though.

More reasons to be optimistic about the future

I brought up the big one, Alpine Park, because I wanted to highlight an example of a previously “sleeping” asset waking up. But that is far from the only reason to be excited about the future.

I for one am ecstatic that Dream is going to start Dream Equity Partners (DEP), its private capital asset management platform. After selling Dream Global last year, Dream’s asset management business is pretty tiny. In the work for that other post I mentioned I estimated the business would receive ~$18 million in fees from Dream Alternatives and Dream Industrial and the trickle of fees it gets from Dream Office. It was actually a little disheartening. I love me an asset manager, so the business being so small weighed on how much I like Dream pretty heavily. Of course, as soon as I made those estimates Dream announced it was starting up DEP, and I was smitten once again.

On the Q2 conference call, CEO Michael Cooper said he was aiming for DEP to be breakeven in three years.

Transcript source TIKR.com

That was a little different than my expectations, but I think Cooper isn’t using any of the margin Dream already earns by managing the subsidiaries (~$7 million/year by my estimate). Regardless, I still think this will be very valuable. Dream’s services are in high demand, as stated in this call, Dream has a track record (a good one at that), and has a lot of the infrastructure and talent to manage these funds already.

Transcript source TIKR.com

I’m basing this on essentially nothing, but let’s imagine the future a bit. Cooper hinted at breakeven in three years, who knows what that would mean for AUM, but let’s say at that point Dream is at $1.3 billion AUM (roughly what Westaim‘s Arena Investors is at, and Arena is around breakeven), and Dream gains $500 million to $1 billion a year in AUM thereafter (at say 1% fees before performance fees). In 6 years DEP could be earning like $20 million, and still growing rapidly. Add that to maybe $10-$15 million from managing the subsidiaries. What would such a business be worth? I would say such a business is worth more than 15x earnings. At 15x Dream’s asset management platform would be worth over $11 a share. While Cooper has stated that Dream will probably participate in DEP funds by seeding them with properties, the business is still pretty asset light and would be one more thing that causes Dream’s NAV to be higher than its book value.

Dream is going to grow book value quite a bit over the next 6 years (you can take that to the bank), when you add the value of DEP and the other management earnings, it’s hard for me to not get excited.

Not that many people care about Dream at all, but the lumpiness of development earnings has been brought up as a negative. That it becoming increasingly mitigated as Dream devotes more and more of its capital to recurring income assets. As it stands almost half of Dream’s assets are recurring income assets, and there are many more projects that Dream is going to hang onto that will start contributing recurring income.

Ignore the terrible highlighting job

Most of those projects are targeting occupancy/stabilization in the next two years, so by 2023 Dream is going to resemble more of a straightforward real estate company, as opposed to the real estate/developer/asset manager chimera it looks like now. At that point maybe Dream starts reporting FFO like other asset managers (Tricon, Brookfield, Melcor) have done since apparently real estate investors can’t get their head around other metrics. Maybe Dream boosts the dividend even more since it requires less cash to develop land and the cash flow it has is more dependable. Maybe Dream spins off another REIT. Who knows, but the company will look very different, almost certainly different in a way that it is easier for investors to see the value they are missing now.

The last thing I’ll mention about the future, that I don’t think enough people are considering, is the incentive fees Dream is set to earn from Dream Industrial at some point in the next five to ten years. I figured in that Dream Industrial post that if Dream sold Industrial in just a couple years, Dream was set to receive something like $220 million in incentive fees. Every year that goes by without a sale, those incentive fees are going to grow. The incentive fees are 15% of AFFO above a hurdle. The hurdle rate goes up by half of CPI annually. I don’t think it’s taking a leap to say even just same property growth would lead to AFFO increasing by more than inflation. Then you add AFFO from future acquisitions, and the AFFO that comes as a result of the eventual sale, and, as much as I’d love for DRM to receive ~$5/share in cash, the best thing to do is to just keep building Dream Industrial. Just know that there is a $220 million asset growing at essentially the same rate as Dream Industrial is, that one day will be realized. I know the market isn’t paying attention to this.

The folly of a NAV target

I want to borrow and riff on a good comment/discussion by reader Rod in the comments of another one of my posts.

The discussion

The discussion came about because reader Fan generously sent me the report of a CIBC analyst, which included a $34 NAV estimate and a price target of $24.

From the report

That price target and Rod’s comment got me thinking. For one, the analysts have to be setting their target based on what they think the stock might be, not based on what they think Dream is worth. I think sometimes investors conflate those, taking an analyst’s price target as both what the stock might get to and what the stock is worth. Back when I cared about analyst targets, I probably did too.

Again, I’m going to forget about NAV and just refer to book value.

If you were analyzing Dream and determined that it is worth some discount to book value, aren’t you implicitly saying:

there is some future end date where the terminal value of Dream is based on book value; and

either Dream is going to grow book value at a rate lower than the rate of return of the market; or

the end date is somewhat near (such that book value growth can’t be the major contributor to shareholder returns) and that the terminal value is also below book value; or

a combination of either point above plus that book value is overstated?

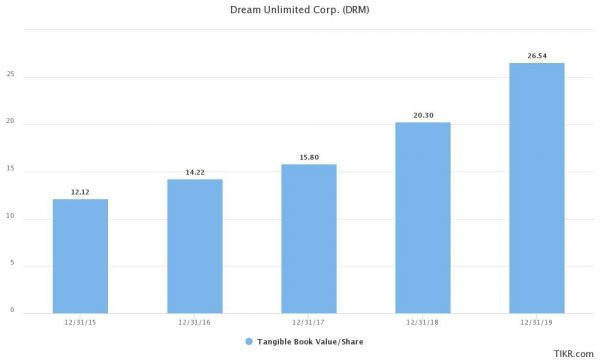

As it is, Dream has been growing book value much faster than the market has grown (in the four years pictured above outperforming the S&P 500 by around 10%/yr), and I’m pretty sure that will continue (you’re free to disagree, it seems like almost everyone does).

If you imagine some fantasy world where Dream always trades at book value, your return as a shareholder would be book value growth plus dividend yield. For most of Dream’s public existence that would be mean returns of like 20%, depending when you bought and sold. Obviously that’s silly, and a public company only provides 20% returns if it is undervalued. Nothing about Dream is unknown, so theoretically Dream should neither over or underperform the market, it ought to be priced now such that it provides a market return over whatever time period.

It goes along with Warren Buffett’s idea (I can’t find the quote right now with quick Googling) of equating a stock to a savings account. If Dream was a bank account with $26.54 (BV at the end of 2019) in it, and it earned interest of even 15%, how much would you pay for that savings account? You’d pay a lot more than $26.54. Maybe you’d pay $30, maybe you’d pay $40 if you knew you didn’t need the money from the account for 10+ years. Maybe you’d pay $50 if you didn’t need the money for 20+ years, etc.

Meanwhile, if you told me to buy a savings account with $26.54 in it, that I had to hold on to for over a year, and it paid say 5% interest, I’m not paying more than $26.54, and maybe I’d offer less than that.

That’s my retort to the first option (second bullet above). What about the second?

I do think that there will come a time when book value is relevant.

I don’t know what exactly will be the cause. Maybe some day Dream is sold, and I know Cooper would require NAV (not book value) or more. Cooper owns almost 42% of the company, so it isn’t getting sold unless he is getting a sweetheart deal.

Another possibility is Cooper one day buys the shares he doesn’t own. Right now Dream, along with Dream Office and Dream Alternatives, are buying back shares hand over fist. I am not going to count the shares bought back, like I sometimes do, but rest assured Cooper’s stake is even higher now. It’s true that if Dream stays this cheap for a long time, Dream probably will buy back enough shares that Cooper could buy the rest of the shares easily. Some might worry about that, but I’m pretty sure Cooper wouldn’t low ball minority shareholders (too badly). Maybe he only pays book value, but that still means a discount to book value would be unwarranted.

Perhaps more importantly though, these terminal events are many years down the road. Even if the final price Dream trades at is a discount to book value, the end date should be far enough down the road that the largest determinant of a shareholder’s return will be book value growth, not the terminal multiple. Thinking of it like the savings account, I would still pay more than $26.54 for the savings account if the deal was it earns 15% interest but I only get 90% of what’s in the account at the end of 20 years. The compound interest makes up for that lost 10%, the opportunity cost of a market return, and a lot more.

The final option, that book value is overstated (so that a discount to book value is not actually a discount to what the equity is actually worth) – I disagree with this premise when it comes to Dream. If anyone thinks the book value is overstated, I’m happy to entertain that position. It seems obvious to me that NAV (aka “true” book value) is higher than book value (aka “accountant’s book value”), so much so that without a convincing argument otherwise I don’t consider it a possibility. This isn’t Brookfield selling assets at IFRS values (and only selling the assets for which they can get IFRS value) to prove book value is real, where you could make a reasonable argument that NAV is lower than book value. The same premise in relation to Dream would be saying that land outside Canadian cities, even if those cities are in Alberta and Saskatchewan, is worth the same as it was 20 years ago. It’s saying that a condo can’t be sold for any margin. I just don’t think that’s plausible.

One other way that Dream will probably start “realizing” book value is through what will probably be a long growing dividend. Dream began paying a dividend last year, and raised it last quarter, in what looks to me like a trend that will continue. As much as I’d rather Cooper use all the cash to either reinvest or buy back shares, when Dream pays out a $0.03 dividend, that cash is not getting discounted by the market, whereas $0.03 of cash within Dream is valued at $0.018 (right now) until it is paid out. As Dream grows its dividend, more cash gets paid out and therefore properly valued by the market.

Yes I know book value goes down by the amount of the dividend, and in theory the multiple should stay the same, but the dividend hardens some of book value, which I think serves to shrink the discount.

If the analysts at CIBC instead were trying to figure out what Dream should be valued at in the market, I think that only a premium to book value would make sense, or alternatively some multiple of normalized earnings.

Now what sort of price target/intrinsic value makes sense? It could be a multiple of book value, where a premium makes the most sense. If you bought Dream for $40 tomorrow, just two or three years of book value growth without the share price going up would lead to your position once again trading under book value. If you paid $40 though, and the stock matched the market’s performance (or even just the real estate sector’s), maybe your P/BV would shrink a bit, but the multiple contraction would at least make a little sense – the company would be growing larger, becoming more like a simple income property holding company, book value growth might be slowing and ROE might be trending lower.

Or maybe a multiple of the normalized earnings shown above makes more sense. In any given year, Dream looks to earn ~$1.50 (not sure how TIKR came up with “normalized earnings”, but they are more or less right on the few I double checked). Would 20x normalized earnings make sense in the current environment? I think so. While normalized earnings per share haven’t grown (they will in the future as Dream holds more income properties, but let’s forget about that for now), a 20x multiple is either fair or low given the occasional windfalls that Dream earns when it sells a large chunk of land, like the big income number in Q1 this year from selling Glacier Ridge, or the incentive fees it earned when it sold Dream Global. Maybe an even higher multiple is warranted because normalized earnings are just the baseline, but let’s just use 20x. That would lead to a $30 target price, and all those windfalls can just be gravy.

However you want to decide your target, a discount to book value doesn’t make sense to me, and I think any sensible target is a lot higher than the stock price now (to their credit CIBC’s target is a lot higher than it).

Reasons to dislike Dream

In the tweet I included above, I was sort of fishing for reasons why people don’t like Dream. While nobody was really able to make a good bear case in my mind, they did point out a couple things that might be weighing on the market’s sentiment about Dream.

Of course Dream’s exposure to office and retail were brought up. It’s a valid point. As I said, I think the market has it wrong with its valuations of office real estate, and good retail, but I do get what the market is thinking.

My first thought was that almost all of Dream’s office exposure is through its 29% ownership of Dream Office REIT, so there is always an external data point for what Dream’s office real estate is worth. But that doesn’t really change anything – the big drop in Dream Office REIT’s unit price definitely accounts for a lot of Dream’s share price decline. I mean, just look at this sentence from the press release announcing Dream’s Q4 2019 results:

As of February 21, 2020, Dream currently owns 17.0 million units or $615.7 million at fair value in Dream Office REIT (a 28% interest, or 30% interest inclusive of units held by the President and CRO) and 16.1 million units or $127.2 million at fair value in Dream Alternatives (a 23% interest), comprising 61% of our market capitalization.

Those 17 million units of Dream Office REIT are now worth ~$340 million. The Alternatives units? $85 million. Their price drops are equal to like $6.60 per Dream share. It’s significant. And Dream does record Dream Office on its balance sheet as an equity accounted investment, so the market does need to correct the difference between the current value of $340 million and the $470 million Dream Office was recorded at after Q2.

Okay, do that though and you knock a little under $3 off book value. The discount is still too great.

As for the retail, Dream really doesn’t own that much retail real estate right now. What it does are trophy assets like The Distillery District, it’s not your average strip mall. The retail can’t account for much of the discount.

However so much of the future developments will be devoted to commercial real estate that you couldn’t blame someone for discounting it. Go back up to that picture of some of the developments Dream is working on. There is enough commercial and “mixed use” that if you think commercial real estate is drastically impaired, you have to reduce your estimate of Dream’s value.

Combine the quantifiable loss of value with the unquantifiable loss, and you probably do account for a lot of Dream’s low valuation.

The other thing brought up is Dream’s debt. The one who brought it up is a debt investor, so he was just bringing it up as a single data point, but he brought up the fact that Dream has $220 million of debt maturing in February 2022. His issue with that was a) it is a pretty large amount, he mentioned it being 25% of the market cap and b) Dream has just $32 million of cash.

He acknowledged Dream almost definitely can come up with $220 million between now and then. Indeed, cash flow will account for a lot of it (Dream brought in $70 million after the quarter ended alone) and Dream is under leveraged enough (27% debt to assets) that it can borrow against another asset (the way it refinanced the Distillery District this quarter) to pay off the facility if it cannot be refinanced or extended.

I am by no means worried about Dream’s debt, but I appreciated the point because if he saw that as a potential negative, others out there are also seeing it.

Dream’s debt has been mentioned to me before. Not the level, but the fact that Cooper took on margin debt and a short(ish) term loan that this person didn’t view as prudent. They were bearish on Canadian real estate, so those forms of debt were more dangerous than mortgages or construction loans. This is another reason I understand.

The debt reasoning is one I actually sort of like to see because it is one that is easy for Dream to fix. All Cooper has to do is push out that maturity, maybe reduce the balance a bit (though I see leverage as very reasonable), and voila, you have what could serve as a catalyst for re-rating. And I have no doubt that Dream can refinance or extend that facility.

In addition to those two “novel” issues brought up, Dream still suffers from views on Canadian real estate, negativity about Western Canada, and now sentiment about Toronto real estate’s future. Throw those together and you have a recipe for 0.6x book value.

I see reasons why those worries are exaggerated, but my reasoning for being long Dream is more about me thinking all of those worries are overblown.

I am confident that offices will still be a big part of running a business in the future. And many businesses will continue to want to rent office space in Toronto.

I am confident that while work from home options may increase the number of people who can live outside of Toronto because they no longer need to be close to work, people are still going to want to live in Toronto. Sure prices could go down for a while, maybe down a lot, but long term there are not enough homes for all the people who want to live in the city.

Western Canada is not dead. Oil is going to keep being taken out of the ground there, and the Alberta economy will keep diversifying. Eventually the beauty of the province, and the appeal of its cities, will be recognized and real estate prices will stabilize or increase.

The debt is manageable, and will be managed.

Conclusion

I know besides me there are about ten people who care about Dream Unlimited, and I doubt Michael Cooper or anyone at Horizon Kinetics is reading this, so I appreciate it if you slogged through this rambling. I started this post with the intention of showing Dream’s a relatively simple value idea, and then of course I added 4000 unnecessary words.

After all this blabbering, what is Dream worth? I really can’t say. It could be $28 (standalone book value), it could be $30 (20x normalized EPS), it could be $34 (analysts’ median NAV estimate), it could be a lot higher. If we work under the assumption Dream can earn double digit ROEs in the future and grow book value in the high teens, you can justify even higher prices. I am specifically not making those assumptions nor do I want to convince you of them. More to the point, I think you have to make wilder assumptions to justify $17 than you do to justify $30.

Dream Unlimited is a fat, fat man. I don’t know if he weighs 300 lbs or 350 lbs or 400 lbs. I know he’s not 175 lbs though. And I know he’s going to keep overeating.

Nice write up. I missed DRM in 2020 (busy with other names) when you were pounding the table. This is one to dig in to and come up with a 5 year hold view. Nicely done!