Algoma Central seems like it would be right up the alley of a lot of people out there.

Algoma Central operates in a simple to understand business. The company has four segments.

The domestic dry bulk segment consists of 18 ships carrying bulk commodities (grain, iron, steel, salt, cement, aggregates, etc) on the Great Lakes, in the St. Lawrence Seaway, and in Atlantic Canada.

The product tankers segment operates 7 tankers carrying a variety of petroleum products (it also operates a vessel owned by a third party). Algoma recently purchased two tankers, has an order in for two newly built tankers, and has 50% ownership in a joint venture that is buying 10 newly built tankers to operate in Europe.

The ocean self-unloaders segment is eight “ocean-going self-unloaders”. Three new ships are ordered which will replace the three oldest vessels in this fleet.

The global short sea shipping is comprised of three 50% joint ventures. NovaAlgoma Cement Carriers owns cement carriers, which do exactly that. NovaAlgoma Short Sea Carriers owns short sea mini bulkers, while NovaAlgoma Bulk Holdings owns handysize bulkers, which are a step up in size from the mini bulkers.

To dumb it down further, Algoma is a marine transportation company with a variety of vessel types, operating mostly in the Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Seaway as well as worldwide through joint ventures, hauling commodities that are integral to the economy.

Algoma has been doing this for over 100 years. It was incorporated in 1899 and began trading on the TSX in 1959. As Algoma is proud to point out, it has a “long operating track record with over 70 years of uninterrupted profitability”.

The company has undergone a lot of change in that time obviously. As an example, take a look at this overview of the company from the 1980 annual report:

Algoma has changed its name and now just operates in one of those five segments, yet even so, the long history is impressive.

As is the continuity of its leadership. In 1980, Henry Jackman was chairman of the board - he was before that as well, that is just the oldest date I can confirm based on some brief looking. Now, his son Duncan Jackman is (and Duncan’s been a director since 1997) and his daughter Trinity is on the board as well. And they have skin in the game.

“E-L Financial Corporation Limited and companies acting in concert with it control in the aggregate 29,340,740 Common Shares (74.2%).”

Great Lakes

Domestic dry bulk is Algoma’s largest business, at least for the time being. In 2023 it was 57% of revenue and 45% of EBITDA. This makes it worth looking at the advantages that lead to this being a good business.

The major one is the unique characteristics of the Great Lakes. There are a lot of locks in this seaway (essentially little sections of water that can raise or lower boats to different elevations.

The Welland Canal locks are long and narrow, meaning that not just any ship can carry cargo on the Great Lakes. A ship fitting the necessities of the Great Lakes can be used elsewhere, but for the most part if you are shipping on the Great Lakes, you are using a boat intended for that purpose. Buying a boat to compete on the Great Lakes would be a large investment then, preventing new competitors. It is estimated that just 10% of cargo ships on the ocean today are capable of navigating the locks.

There are also of course two different federal governments to contend with, which adds a regulatory burden. For instance, the Jones Act stipulates that vessels carrying goods between US ports must be built in the US, registered in the US, crewed by mostly Americans, and owned by US companies with at least 75% US ownership (note that Algoma doesn’t fit the bill, hence it can’t do US to US freight). That greatly limits players in the region. As far as I can tell, there has been just one ship built in the US since 1983 to start service in the region. Another example - to operate on the Great Lakes you must have a registered pilot and the system is onerous enough that the Great Lakes Ports Association lists pilotage as a key issue limiting competition. Algoma meanwhile has its own pilots. The Coasting Trade Act mandates foreign vessel owners get a license to operate in Canadian waters and use Canadian crews, again limiting what competition is willing to come compete with Algoma.

Coordinating with two very different federal governments, both with their own laws and regulations, plus eight state and two provincial governments, means many shippers won’t bother to enter the market. The Jones Act, the Great Lakes pilotage regulations, the Coasting Trade Act, are just a few prominent examples among many.

The shortened season is another barrier. The Great Lakes freeze. Icebreakers can allow winter shipping, but there is a shortage of icebreakers. Depending on the winter, the shipping season may only be 9-10 months long, and the Soo Locks (which separate Lake Superior from the lower Great Lakes) closes each winter by law. These winter limitations certainly discourage new competitors.

The barriers to entry are seen in the limited number of carriers operating on the Great Lakes. There are only about 20 fleet operators, and Algoma is the largest of those, and one of the oldest. Surely the customer relationships and operating track record Algoma has built up serve as a competitive advantage as well.

Because the Great Lakes are fresh water, boats last a very long time there. Algoma is still running 5 vessels built before 1980, and there are many boats on the Great Lakes older than that. It has typically operated its domestic dry bulk vessels for over 40 years, and the average age of the vessels now is under 20. This fleet should provide steady to earnings for years to come.

Product Tankers

This is where Algoma’s growth is coming from.

Entering the year, Algoma had 17 new vessels ordered and being built. 5 were replacements for the existing fleet (2 for domestic dry bulk, 3 ocean self unloaders), and 12 were new vessels to grow the company. All 12 “growth” vessels were product tankers.

In partnership with Irving Oil, Algoma is buying two ice class tankers to serve Irving’s refinery in Saint John, New Brunswick on long term time charters. The other 10 new vessels will be operating in Northern Europe in a new joint venture called FureBear, with Swedish company Furetank.

Additionally, this year the company bought two tankers that were built in 2009 to grow the fleet more, costing ~$37 million.

All this means that by the end of 2026, without any new purchases, the product tankers fleet will have grown from 7 tankers, to 11 fully owned tankers, and 50% of a JV that owns 10 brand new tankers and 2/3rds of an interest in an 11th.

While the segment is currently Algoma’s smallest by revenue, that should change. Tankers is clearly where management sees value and growth opportunities right now. This quote from Furetank’s CEO might shed some light on it:

“We see the upcoming phasing out of older tonnage in the market far exceeding the amount of newbuilds underway.”

In 2022 and 2023, with roughly 118,000 MT of deadweight tonnage, Algoma earned ~$10 million and $15 million in earnings respectively, with roughly $25 million in EBITDA both years.

If we assume that the capacity that Algoma is adding in the near future (capacity in 2027 will be ~315,000 MT DWT with just today’s new orders) is just as utilized and profitable as the old capacity, segment earnings will grow to over $33 million, and EBITDA to ~$64 million. That doesn’t quite match the size of the domestic dry bulk segment, but it’s close. And the fleet will be renewed from its current average age of ~16 years to just under 10 years.

We know that the two Irving tankers will cost ~$63 million each, and my best guess is that the the new FureBear tanks cost roughly the same:

The financials of the joint venture provide another way of estimating what these new vessels could earn. We can see that in Q1 the product tankers joint venture added ~$60 million in PP&E, and ~$30 million of debt. 9.5% returns on equity are the stated goal/hurdle of management*, and it appears that this JV will finance its ships with 50% debt. If we make an assumption that all the tankers will be financed similarly, and the 9.5% ROE is achievable, the 12 new tankers will cost Algoma ~$430 million at its share, be financed with $215 million of debt, and be expected to earn ~$20 million.

*It’s worth noting he past three years, Algoma has earned returns on equity of 11%, 14.6%, and 13.7%. ROEs had been lower before that.

Both methods of estimating give similar earnings numbers, so I’m pretty confident in that growth number.

Valuation

No matter how you look at Algoma, it’s easy to see that it’s pretty cheap.

The easiest way is simply the P/E multiple. In 2023 Algoma earned $2.00 per share. The number was similar in 2021 and in 2022, after removing some one time gains, Algoma earned $2.40. Algoma’s outlook suggests that 2024 will offer a similar to slightly higher number. And as mentioned, Algoma has 12 new build tankers being delivered by 2027, and two tankers it purchased second hand earlier this year, which will contribute to earnings growth.

For this earnings power of consistently $2, and likely growing to close to $3 in 2027, the stock is trading hands for under $15. Call that 7.5x earnings for a company with a lot of competitive advantages in its main business, earnings 10% returns on equity, led by long term shareholder oriented management.

Similarly, we can see that over the last four years, Algoma states that it has earned $100 million in free cash flow each year, with the exception of 2023 when the company “made environmental investments in fleet upgrades such as carbon reducing fuel efficiency technology, ballast water treatment system installations, and closed-loop exhaust gas scrubber upgrades”. This increased capex on its existing fleet led to Algoma’s reported free cash flow dropping to $65 million. Algoma’s capex to maintain its fleet the last four years has been $35 million, $16 million, $10 million, and $22 million. Meanwhile depreciation is ~$65 million each year. I suspect that maintenance capex likely is lower than depreciation, but also that less than $20 million is artificially low. If we revise up capex a bit, we still get Algoma trading at something like 8-9x free cash flow.

Finally, we get to a method of valuation that Algoma is fairly unique in bringing up:

“I made a fortune buying real estate at below its replacement cost, which therefore guaranteed me that the guy couldn’t build something across the street at less than my basis”

- Sam Zell

Algoma claims that the replacement cost of its ships is ~$2 billion, with $1.3 billion being the replacement value of its domestic dry bulk fleet. At current prices, buyers of Algoma stock are buying its fleet for an enterprise value of just $1.1 billion. Given the age of the fleet, perhaps that is a fair value for the ships - if the ships brand new would be worth $2 billion, how much are the ships worth if they are on average ~15 years old? - but as Sam Zell says, buying Algoma’s fleet for much less than its replacement value means it is harder for another operator to come in and undercut Algoma and really hurt its business.

E-L Financial

What to make of the very high ownership of E-L Financial.

For one, E-L is a long term investor - the E-L entities have owned Algoma for decades. You don’t have to fear that Duncan Jackman is going to wake up tomorrow and sell some shares of Algoma. E-L and the Jackmans have a long history of trustworthy public company stewardship.

Two, E-L does not appear to be using Algoma for any nefarious purposes. Related party transactions are non-existent. Algoma is clearly still investing in maintaining its fleet and growing, as evidenced by the large commitment to the FureBear JV.

Three, capital allocation, which of course would be highly influenced by E-L (even if that fact goes unsaid), has been a pretty even mix of growth, buybacks, and dividends lately. Regular quarterly dividends are a stated objective of Algoma, and Algoma has done a good job of growing that dividend. As discussed by Nelson here, Algoma’s dividend has nearly tripled in the last ten years, and Algoma has paid three special dividends, totalling almost $5.00, in the last five years. And despite the clear preference for dividends, Algoma still finds cash for buybacks. Over the last five years, Algoma has repurchased ~1.2 million shares (~2.8% of current shares outstanding). Shares outstanding are up because of a convertible debenture maturing recently with shares trading above the conversion price.

Conclusion

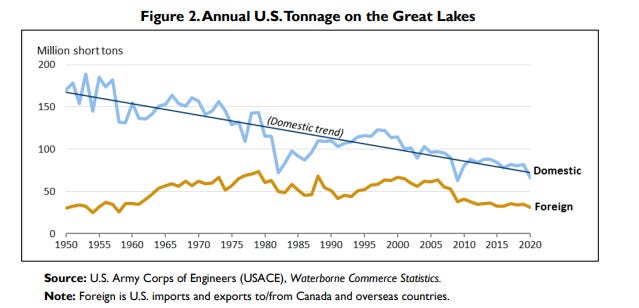

Algoma isn’t for everyone. I know many may not get excited by a company aiming for 9.5% returns on equity. Even if the Great Lakes shipping business is a strong one with barriers to entry, it is still a declining industry.

That said, there are currently arguments being made that shipping on the Great Lakes could be a tool in the fight on climate change:

I don’t think an investment in Algoma needs a Great Lakes shipping renaissance to succeed though. A 10% ROE purchased at ~7x P/E would check the boxes of a lot of investors. A lot of folks will be happy with a 5% yield with a low payout ratio and growing dividend. If that’s you I hope my little writeup here has helped. I think there’s certainly an opportunity that Algoma offers very satisfactory shareholder returns.

Finally, someone has talked about a stock that I actually own. I feel like a younger Warren Buffett now..

Thanks for this writeup; you did a great breakdown of a company that no one seems to see.

I love reading about companies like this even if it’s not a good prospect for me. Thank you for sharing your write up.