I’m a homeowner in Canada*, a rural Ontario town about two hours from Toronto (with no traffic, which obviously never happens). I’m also heavily invested in a Canadian real estate developer and property owner, as those reading this are aware.

*A bit of personal news that you won’t care about, I’ve recently purchased a house and am in the process of selling mine, so I have some on the ground insights into this market right now as well.

I like to think of myself as a rational thinker and an empathetic person, but I realize the two facts above could cloud my judgement, or at the very least cloud your judgement of my thinking regarding the housing market. I’m going to do my best here to prove my rationality, and present both sides of the argument. As I contemplated the idea for this post in my head I have the intention of not even taking a side in the “what housing prices will do” debate, though my intentions and the finished product may differ. I’m also only going to tangentially tie this to Dream Unlimited at the end, as it was reading a section of Dream’s 2023 Q3 report that made me think about this.

If you haven’t been paying attention, it seems like Canada’s federal government (in power since 2015) has finally realized that there is a housing affordability issue in Canada. This is of course insane:

Regardless of how long it took the government to realize this* or why (it was only when it became the top polling issue affecting the government’s chances at re-election), the federal government has finally gotten on board and is now interested in improving housing affordability.

*I want to remain firmly on the political fence here - the current Liberal government has obviously been a trainwreck for housing affordability, as you can see in the above chart, but housing prices started pulling away from incomes more than 20 years ago, and Stephen Harper’s Conservative government only saw the issue get worse during his ~10 years also.

This has made house prices much more of a talking point than they already were. The Prime Minister is on television everyday talking about housing prices (as opposed to whatever he was talking about before). Sean Fraser is a household name now. It’s the kind of attention that should have been paid to this issue 10 years ago. And in the governments defense, they’ve made some good and needed moves, among them, making (more) low interest loans available to developers, creating a fund to build affordable housing and removing the GST on newly built rentals.

For the first time in this housing crisis, it seems like there is a real push to affect the supply of housing at the federal government level. Or at least the government is paying lip service to the issue.

There are just two problems:

It hasn’t made a difference to housing starts yet.

The demand side of the equation is not being adequately addressed, if you can say it’s being addressed at all.

Look at this chart of Canadian housing starts over the past five years:

Despite it becoming clear that builders need to build more homes to make homes more affordable, housing starts are only marginally up since 2019, and actually down since the boom times of 2021 and 2022.

That makes a lot of sense when you look at interest rates:

There’s only so much the government can do (though we aren’t close to approaching its limits yet). Debt is a huge part of building housing. Interest is one of the biggest expenses a developer pays. We’re talking developers here, so let’s look at a small sample of publicly traded developers:

In the nine months ended Q3 2023:

Dream Unlimited’s development segment’s interest expense increased 57% year over year (YoY).

Melcor Developments’ finance costs increased 80% (YoY).

Genesis Development’s finance costs over 300% (YoY).

I’m not claiming these are perfect representations of the effect of interest rates on developer profits (Melcor’s number for instance includes mortgage interest for its REIT that I couldn’t (or didn’t want to) separate out). Even so they serve as an indication, and those represent huge hits to the profitability of a new build.

Government action is butting against interest rates and the economy (a reason cited by CMHC for housing starts weakness). But “who will build the houses” is also a huge problem.

In October of 2022, CMHC released a report on Labour Capacity Constraints and Supply Across Large Provinces in Canada. The whole report is interesting to someone like me, but to save you 17 pages of reading. This is the bottomline CMHC found:

There are not enough people who can build homes and address the housing supply gaps that exist mainly in Ontario, BC and Québec. Labour capacity will be a big problem and it might make housing less affordable.

It also included this helpful chart:

Without getting too into the weeds of their methodology, those best case scenarios are unlikely to be hit (they would mean both greatly increasing how many people work in construction and improving each worker’s productivity), and yet if we hit those best case targets, among the four largest provinces only Alberta would meet its target supply of housing, and Canadian housing as a whole would likely become much more expensive.

While on the topic of weak supply, I would be remiss if I did not mention development charges and municipal taxes.

I have been trying to be very clear that it is the federal government that is making the noise about building more. Municipal governments remain a foot on the brake.

Take a look at this graphic:

Then look at this:

https://twitter.com/ronmortgageguy/status/1755987477121167615

Toronto is not Canada, but it’s hard to deny that Toronto increasing taxes and fees on new development like this has cost Canada a lot of new homes. It’s definitely contributed to Toronto’s insane housing prices, the outrageous prices in areas surrounding Toronto (as people who want to live in Toronto are forced to settle just near Toronto), and probably indirectly to housing prices all over the country.

And lest you think it’s just Toronto, Vancouver recently proposed tripling the fees it charges developers to build. Sean Fraser was in the news stating that the increase to development charges could reduce development, and threatened the city with taking away any funding from the new federal housing fund.

That is two of Canada’s three largest cities actively suppressing development, and not showing any particular sign of letting up.

There were a few things I wanted to talk about regarding housing.

The government has now decided the supply side of the supply and demand equation is important to incentivize. The government is throwing a lot of its weight, and money, behind the platform of building more houses.

For a few reasons - I specifically wanted to highlight interest rates, labour shortages, and development charges - developers have not ramped up supply the way the federal government wants them to.

Demand growth.

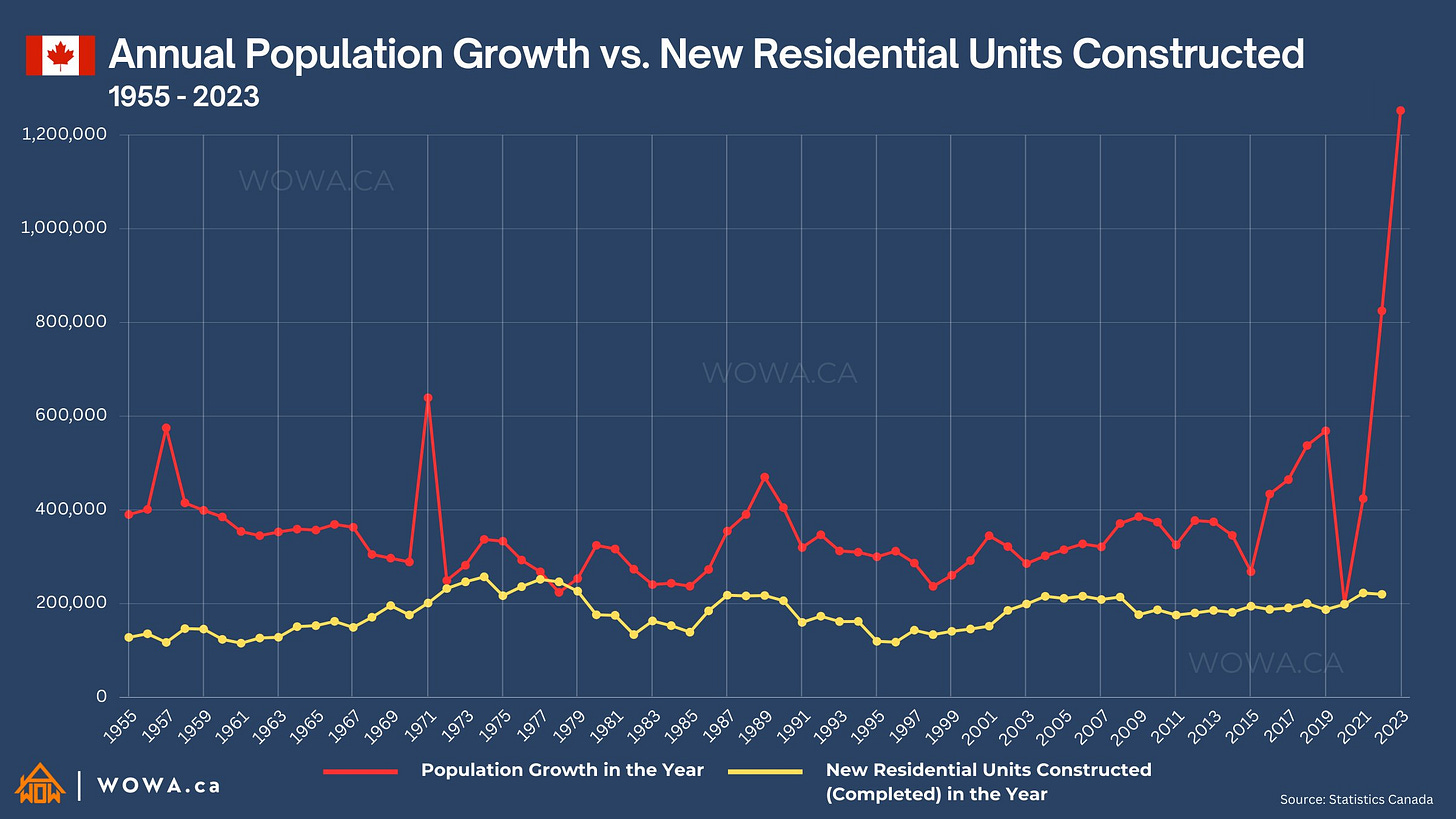

For decades, the population grew roughly 300,000 people per year (sometimes up to 400,000, sometimes down around 200,000). During that time, Canada completed somewhere around 200,000 residential units each year.

Starting in about 2000, housing unit completions really stabilize at 200,000. It’s kind of crazy how stable that number is. Population growth ticks up and it’s closer to 400,000 than 300,000, especially after 2007*. Go back up and look at housing affordability over that time, and you’ll see that the stable 200,000 new homes was not enough to keep up with the population growth.

*Again for balance I’ll note that Stephen Harper was leader from 2006 to 2015 when population growth edged a little higher, because I’m going to have to shit on the current government pretty hard.

You’d think one residential unit per 1.8-2 people or so would be enough to at least keep affordability steady. And maybe it is. Affordability could have gotten worse for a variety of reasons:

maybe the units being built weren’t where the population grew - 10,000 houses being finished in Cape Breton won’t help affordability in Toronto.

maybe the product mix being built wasn’t suitable for the population growth - eg. one bedroom condos are not the right kind of house to support a 2 person household (yes I know it can be done, you get the point) - hence we needed more residential units per person.

maybe low interest rates allowed people to pay more for houses.

maybe there was the ever touted “financialization” of housing going on.

maybe it was the foreign buyers that so often got blamed.

maybe government policies stimulated demand for housing in excess of supply.

maybe, going along with the right product mix idea, a lack of investment in social housing hurt affordability at the low end, forcing lower income folks to push up the price of lower end houses.

maybe one hundred other reasons.

I’m not here to argue that time period. I’m talking about now. And the graph makes the problem very obvious. 200,000 new houses each year was not enough supply to keep affordability steady while growing the population 400,000 people per year. Then Justin Trudeau was elected, and the population started growing even more, with no corresponding increase in homes being built (due to labour constraints and more, there’s no way enough homes could have been built). That was problem enough.

Then after COVID, the population exploded. The Liberal government ramped up immigration (mostly non-permanent residents (NPRs) to an unprecedented degree.

Canada's population was estimated at 40,528,396 on October 1, 2023, an increase of 430,635 people (+1.1%) from July 1. This was the highest population growth rate in any quarter since the second quarter of 1957 (+1.2%)… Canada's total population growth for the first nine months of 2023 (+1,030,378 people) had already exceeded the total growth for any other full-year period since Confederation in 1867, including 2022, when there was a record growth.

Source: StatsCan

We saw earlier that 1 residential unit per 2 people was not enough to improve housing affordability, so how many units do we need to build to absorb the extra 1 million people in this country through just nine months of 2023? An astronomical number that Canada has proven unwilling or unable to build.

Luckily for Canadians wanting to buy a home, the effect this rampant population growth is having on home prices is now realized in the broader consciousness, and people are talking about it.

Government was warned two years ago high immigration could affect housing costs

Housing crunch driving more Canadians to say immigration is too high: survey

Unfortunately for Canadians wanting to buy a home, for all the government has talked about building more houses, it doesn’t see the effect it is having on demand for housing:

Canada aims to welcome 485,000 new permanent residents in 2024, 500,000 in 2025 and plateau at 500,000 in 2026

Source: Federal government

Note that is just the target for permanent residents. There is no target for non-permanent residents and the government hardly seems to care about the number of NPRs. In January, Immigration Minister Marc Miller (a name I only know because of how much the government’s immigration plan has been lambasted) said the government may rein in non-permanent residents, not that the government will, while defending the broader immigration plan.

Summing up, the current consensus in this country is Canada needs to build more houses. The solution we’ve come to is we need to create more housing to improve housing affordability, which is at the top of mind for most Canadians.*

*Reducing everyday costs, inflation and interest rates, access to affordable housing, and homelessness I would argue all tie into the housing issue, so I’m claiming it as Canadians’ top priority.

Several federal government actions have been taken that should improve the ability of developers to build housing while improving profitability, namely the GST rebate, the low interest loans, and the affordable housing fund. Meanwhile, the government has seemingly made housing affordability a top priority, so I’d bet on more actions being taken. And the voices of those in the housing and development industry are getting through to the right ears; the GST rebate in particular seems to have been an action lobbied for by the industry.

And yet, a few solvable problems are still either keeping builders from building or affecting profitability.

Interest rates are high, and clearly are affecting willingness to take on debt to build housing. When it happens is obviously up in the air, and could be later than most are expecting, but clearly people are expecting interest rates to drop in the coming years, which would be one source of relief. The other is the expansion of low interest government loans/interest rebates or some such thing, which the government has stated is a low cost way to boost building.

Development charges in some of the obvious places to build housing (desirable cities to live in) are still a major impediment to building. Toronto had a recent 49% increase in its development charges, made under a different mayor, which could be on the table to be reversed or rectified somehow. Sean Fraser has shown a willingness to discuss development charges with cities, and incentivize lowering or at least not raising development charges. Is there a carrot that could be offered to Olivia Chow, or a stick that could be removed, that would make her reconsider the city’s current fee structure on development? It strikes me as probably one of the next hot button issues.

The labour shortage is much harder to solve, or at least will take longer. Let’s skip that because I believe that the construction industry can build more with the current labour force if the financials made more sense.

The current rezoning and approval process, where it takes many years to take a piece of land and turn it into a house for someone to live in, or even a piece of land where you’re legally allowed to start building something, is ripe for reworking. The government has done a little bit to alleviate this issue, through the use of Housing Accelerator Fund funds, as seen below. It’s not much, and not very concrete, but it’s a step in the right direction and larger steps/more focus could be coming.

Between the current actual government actions, and the actions that could logically be taken (above not being exhaustive), I think the business of building houses is set to become more attractive. Builders are finally being seen as an integral part of the solution to the housing crisis.

On the other side of the coin, the demand side of the housing crisis is not being adequately addressed, nor does it seem possible for the supply demand equation to become more balanced simply by adding supply. There are barriers to entry that shouldn’t allow an irrational competitor to come in and wreck selling prices. To name just one, there isn’t enough labour, and probably won’t be for a long time.

we estimated that an additional 3.5 million housing units beyond what we projected would be built anyway under our “business-as-usual” (BAU) scenario would be needed by 2030 to reach this affordability target. Those 3.5 million additional units are what we call the “housing supply gap.”

Source: CMHC

Of course, there is a big gap between CMHC’s affordability target (affordability returning to 2004’s level) and our current affordability, that house prices could drop even if we end up only 2 million homes short, or anywhere in between 0 and 3.5 million. The point remains, the supply gap is so large that building could ramp up substantially before selling prices drop enough to make building unprofitable. And builders aren’t dumb, unless construction costs go down and/or development charges and/or interest rates, they aren’t going to build unprofitably.

Supply cannot increase enough. Demand will remain high. And everyone in power is searching for ways to make builders build more (mostly through ways that are making it more profitable), including ways to stop/reduce a few of the industry’s current biggest impediments and costs.

That seems like a pretty good environment in which to own a real estate developer eh?

As at September 30, 2023, our GTA and National Capital Region pipeline across the Dream portfolio is comprised of over 26,800 residential units and approximately 4.0 million sf of commercial/retail GLA.

We currently own approximately 8,800 acres of land in Western Canada, of which 8,500 acres are in nine large master-planned communities at various stages of approval. With our land bank, market share, liquidity position and extensive experience as a developer, we are able to closely monitor and have the flexibility to increase or decrease our inventory levels to adjust to market conditions in any year.

Source: Dream Unlimited Q3 2023 MD&A

Dream is one of the largest land owners and developers in Canada, yet even if it develops every acre it owns at 5 units per acre in the next 6 years and all the residential units in Ontario finish by 2030, we’re still only talking 71,000 homes being built. It’s a drop in the bucket compared to the 1.5 million homes Canada expects to build over that time frame, and the 5 million homes needed.

It owns a lot of land at a low cost basis as it bought most of the land in the 90’s and early 2000’s. It has a lot of approvals already done, it has construction started on thousands of homes. It has proven to be a preferred partner when governments are looking for affordable apartments to be built. It has cash flow outside of development and assets to sell to reduce debt while rates are high (now), and borrowing capacity to borrow if rates go lower or if low interest loans become available. Dream seems ideally situated to current conditions.

On the one hand, Dream states at the bottom of this slide that development is expected to become a smaller portion of its business. You’d think that would put a damper on the previous 3000 words I had written about how the current environment seems ideally suited for a developer. Why focus on it so much if the company isn’t?

I’ve gone over several times, either on this Substack or on Twitter, the fact that Dream is shifting away from being a developer and to deriving more of its value and income from recurring assets. There’s nothing special about that insight, the company has been saying it for years and has mostly made good on that promise. The current goal is now to have 70% of the net asset value (NAV), and 70% of income coming from recurring income sources in 2032. As I have stated before, I firmly believe should this happen, Dream should rerate to a much higher percentage of its net asset value. Whether that be 70% or 100% or more, I don’t know, but from what I’ve seen of real estate owning peers, asset management peers, etc, the current 40% or so should not be the norm in 2032.

Instead, this time I wanted to focus a bit on the development side. As the slide above shows, four of Dream’s seven listed business drivers are at least tangentially related to the housing issue (arguably the fair value of its investment properties would be as well). Depending on how the current crisis shakes out, the above targets become either more easily achievable or quite beatable.

If builders are incentivized to build, selling 900 lots and 30 acres obviously becomes easier. And if the incentive is great enough, if other costs involved in building go down, the net margin on land going up 3% is not outrageous at all.

With the sales tax rebates in place, governments working on fast tracking approvals, and any other changes, completing 500 apartments each year is attainable.

How much do the government’s actions affect completing projects on time and on budget? Quite a bit right?

Similar to the first point, if land is in higher demand, if builders can build more profitably, land in Western Canada appreciating 4% does not seem too ambitious.

Conclusion

Hopefully I don’t come across as having a view on which direction house prices are going to go, or rents for that matter. I really don’t have one. But I do think prices coming down substantially will be hard, given the factors I’ve discussed. I also think prices going up too much from here is tough too. I know far too many people priced out of the market, and aren’t particularly close to being able to buy a home. I get markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent, bubbles can last longer than…, blah, blah, blah. That’s why I am not one to predict prices will go down simply because prices are high.

The usual market mechanism is high demand creates high prices which creates high supply (and/or low demand) and then prices go down. For a few reasons, that relationship is broken in Canada.

Maybe prices go down. Maybe they go up. I’m not making a call.

What I am saying is the confluence of factors in this market seem ideal for a developer. And I happen to know a developer valued in the market at less than half the value of its assets, which has recently sold a large asset at approximately its holding value (Arapahoe Basin), that has other things going for it but also stands to benefit from this developer friendly environment.

I am less familiar with the other public Canadian developers, but a similar post could surely be written about Melcor and Genesis and probably a bunch of REITs with large development pipelines (SmartCentres, Morguard, First Capital, Riocan, etc), if Dream Unlimited (or Dream Impact Trust which is a more leveraged bet on this environment) isn’t your thing.

Tyler, thanks for the writeups on Dream. I’ve done very well with them. Up 50-60% in different accounts!

In your past tweets, tou have mentioned Melcor development, mrd.to.

Do you have a position in them. The tailwinds helping drm.to should also be great for mrd.to.

Their REIT takeout seems to be a positive as well.

Any insights you have on mrd.to would be appreciated as its hard to find much analysis on them.

Cheers

Tyler, curious about your home purchase: how much it was as a percentage of your net worth and how you justified it from an asset allocation perspective (concentration risk, potentially flat returns going forward)?