Premium Brands Holdings seems like it should be so much more popular than it is. It’s very informal, but my “survey” of knowledgeable people (and even some not so knowledgeable people) shows very few mentions of Premium Brands given:

It’s a pretty large company with a $4 billion market cap

It’s trounced the TSX and even performed admirably against the NASDAQ 100

The CEO talks a very good game.

That last point is worth digging into because while I was researching this company, I chose the probably less than ideal method of reading all of the CEO’s letters first, before really digging into the financials or anything. Please indulge me* in a few quotes from these letters written by CEO George Paleologou:

*Upon proofreading I see that this isn’t a few quotes. It’s a lot of quotes. While I obviously think they add something to the post, I’ll understand if you want to skip them/some. TL;DR - Premium Brands acquires companies, lets their entrepreneurial management teams run their business how they want to, while giving access to a large company’s resources. It invests for the long term and aims to earn 15% on its capital.

Another key element is the entrepreneurial culture in the DNA of all our businesses as well as our organization as a whole. This culture creates an environment where people are not afraid to take calculated risks and, most importantly, are not afraid to fail. Failure is part of the product development cycle and is even more common when focusing on white space rather than the more common strategy of incremental change. We have a healthy appreciation of failure and view it as an integral part of a process that often creates great insights, learning moments, and ultimately better decision making. We are, however, always careful to ensure that the risks we take when investing in new initiatives are manageable and do not expose our company to any unacceptable potential liabilities.

2024 letter

I cannot stress enough that our decision-making processes are based on long-term considerations and, more specifically, creating long-term sustainable value for our shareholders. We never have and never will make decisions based on short-term focused objectives. This perspective is what has driven our past success, including generating a compounded return of more than 18% for our shareholders over the last 20.5 years, and gives us the conviction to make significant capital allocations despite the short-term negative impacts.

2024 letter

We fully appreciate the scarcity of capital and the trust we have been given in managing it for our shareholders. Correspondingly, we hold ourselves and our partner entrepreneurs to the highest standards of stewardship in preserving and investing the capital entrusted to us.

2022 letter

During these volatile times it would be very easy to improve our results by pursuing short term focused strategies such as laying off core groups of employees, cutting back on innovation, cheapening product formulations, pursuing noncore product opportunities, shortchanging our supply network, reducing investment in our operations, etc. Over the years we have seen many food companies go down this path, both in good and bad times, with the common result being that it never ends well – we often see this mistake being made by private equity groups that are new to the food space. Their misfortune often ends with misallocated resources, catastrophic supply chain disruptions and/or the destruction of core cultural values. Hence, while we could easily boost our RONA through short-term focused strategies, we do the opposite and continue to invest in our people, supply chains and operations with a razor-sharp focus on maximizing long-term value creation.

2021 letter

We view FCF per share as one of our most important metrics as it captures the impact of both our operational and finance strategies and highly correlates with the creation of shareholder value over the long term (see chart below). It is for these reasons that all our senior executive incentive programs incorporate this measure – at the Premium Brands corporate office it generally determines 80% of a senior executives’ incentive compensation, including my own.

2021 letter

With only the rare exception, all of our capital allocation decisions are based on an expected internal rate of return of 15% or more (after tax and excluding the use of debt) using business models with 10-year-plus time horizons. That is, we invest for the long term. In the case of acquisitions, it can take three to five years to transform an acquired company from good to great and this can negatively impact our short-term results. But our record shows that, over the long-term, we have consistently delivered on our 15%-plus return objective.

2020 letter

At the Premium Brands level, we do not acquire businesses to rationalize them, restructure them or integrate them in the pursuit of short-term cost savings. We are allocators of capital in the specialty food space and focus on creating value over the long-term – our business plans generally span ten years or more. We only invest in areas of the food space about which we are passionate and of which we have a deep understanding, then further narrow our investments to those businesses with best-in-class management teams who will fit into our culture. Sometimes this means walking away from a transaction that may be considered a bargain based purely on financial metrics.

2020 letter

The PB Ecosystem is a core strength of Premium Brands and is what makes us somewhat unique in the food world. The core to this system is the development of resources for, and connections among, our different businesses that can be leveraged by individual management teams to make their respective businesses stronger. These resources encompass basic tools such as access to corporate procurement programs and sophisticated financial modelling; to more intangible things such as peer supported decision-making and the sharing of best practices.

While some of the resources in our PB Ecosystem are relatively unique to our industry and others may be less so, what truly makes the PB Ecosystem distinct is that it is up to individual management teams to choose how they want to leverage the ecosystem to make their own businesses stronger. This not only creates value by ensuring that each solution is perfectly fitted to the individual business but, more importantly, it ensures the preservation of the entrepreneurial spirit that we hold so dear. The decentralized nature and entrepreneurial focus of our ecosystem is what truly makes Premium Brands unique and antifragile and is what is missed by almost all other major organizations. As I mentioned earlier, the combination of a talented entrepreneurial management team operating in a decentralized environment with access to the resources of a much larger organization is a formidable competitive advantage and a unique point of difference

2019 letter

There were several other exciting acquisitions we completed in 2018, however, the final one I want to highlight is Country Prime Meats as our history with CPM perfectly exemplifies the ethos and spirit of Premium Brands. CPM was founded by Reinhard Springmann in 1996 and today is operated by his two sons Markus and Peter. The company actually indirectly joined our ecosystem when we acquired Freybe in 2013. The Freybe and Springmann families shared many common values, including an unwavering commitment to quality, so it was not surprising that CPM was an important co-packing partner to Freybe. Similarly, it was not surprising that shortly after we announced our purchase of Freybe that Reinhard requested a meeting with me to discuss the future of our relationship. He was concerned that we would bring the products they were producing for Freybe in-house resulting in the loss of almost 95% of CPM’s volume. At that time, we could have easily transferred production of these products into one of our plants, which would have resulted in immediate cost savings, i.e. a short term earnings bump, however, based on our long term vision for the meat snacks category, and our interest in further developing our relationship with the Springmann family, I assured him that not only was our business with them secure, but we would work with them to continue growing their production volumes. Furthermore, I told him that instead of thinking about reducing their capacity they should be considering possible future plant expansions.

2018 letter

My career in the food business began at a western Canada based pork commodity company called Fletcher’s. At the time Fletcher’s operated four facilities: two hog processing facilities, one in Red Deer, Alberta and the other in Langley, BC; and two mainstream processed meats facilities, one in south Vancouver and the other just south of Seattle. The Red Deer facility processed 4,000 hogs per day and sold pork globally while the Langley facility processed 800 hogs per day and catered to niche ethnic markets in BC’s lower mainland. The Red Deer facility, which was much larger and more efficient than the Langley facility, constantly struggled to make money as pricing for its products was determined by global balances or imbalances in the supply and demand for its commodity pork products. Comparatively, the Langley facility always made money as it produced specialized products for niche markets.

At some point, as part of a strategy to improve the competitiveness of the Red Deer plant, we decided to expand its scale and invest in state-of-the-art processing equipment. In conjunction with this, we accepted an offer from a local businessman to sell the Langley operation. We then proceeded to spend $40 million on the Red Deer plant and while the project came in on time and on budget the operation’s financial results continued to be underwhelming. We achieved the expected efficiency and product quality gains, however, we were still producing commodity, non-differentiated products that were being sold at prices determined by factors beyond our control.

In retrospect, we should have sold the Red Deer facility and kept the Langley facility, i.e. we should have sold the commodity focused business that was a price taker and instead dedicated our capital and efforts to the niche focused business that was a price setter. This was one of my first real world business lessons, namely the importance of selling differentiated products at fair prices and margins rather than being a price taker and subject to forces outside our control. To this day this hard lesson is at the core of every capital allocation decision we make.

2017 letter

An entrepreneur who joined us a few years ago called access to these resources the “Premium Brands Advantage.” I cannot stress enough that it is not our corporate team but rather our partner entrepreneurs that leverage the Premium Brands Advantage to grow and strengthen our many food platforms. We are not an intrusive acquirer nor do we have a centralized vision and/or structure. When we invest in a business our first priority is not its integration into a corporate system, but rather to build trust with our new partners and to introduce them to our resources including global buying abilities, access to capital, sophisticated information systems, complementary businesses and most importantly, a talented peer network. From there it is up to them to leverage these resources to accelerate the creation of long-term sustainable value while staying true to the core principles that made their businesses successful in the first place.

2016 letter

Our core strategy of building balance into our business and of managing it in the long term best interests of our shareholders also applies to our management compensation strategies. This is why we do not have, nor do we ever plan to introduce, stock options or other similar forms of compensation. Our view is that for companies in mature industries it is too easy for these types of compensation arrangements to encourage management teams to make decisions that are not about balance and long term sustainability, but rather about what drives a company’s share price in the short term. Instead, we encourage our managers to own Premium Brands shares and even incentivize them to take their annual bonuses in shares. This ensures management’s interests are fully aligned with those of our long term shareholders.

2015 letter

HEY TYLER I COME HERE TO READ YOUR THOUGHTS. IF I WANTED TO READ THOSE LETTERS I WOULD JUST GO READ THEM.

I hear ya. But if you read those quotes (or just trust me on it), and combine that with Premium Brands’ shareholder returns over the years, you’d understand why the CEO’s letters had me wondering why nobody ever talks about it.

It could be that Premium Brands has pretty low margins in a relatively boring business:

It could be that the stock has gone nowhere for 7 years now:

It could be a lot of things.

Since you might not know much about Premium Brands, allow me, and not the CEO, to tell you a bit about it.

The company has two reporting segments. Its specialty foods business is an assortment of food manufacturers who sell their own branded products, sell their products unbranded to customers to resell, and do private label manufacturing for customers. Its “premium food distribution” segment wholesales and distributes food. The seafood processing business is also under this segment.

Premium Brands is a very acquisitive company:

In the CEO’s own words, the company is not a “roll up”. Premium Brands is a decentralized company, not integrating the companies it acquires but allowing them to run independently, while giving them access to the “Premium Brands Ecosystem”, ie. the resources of a large company (access to the distribution business, procurement volume pricing, knowledge of markets, administrative services, etc).

As you can imagine, the specialty food business is the better one. It has shown exceptional organic growth and has higher margins…

And it is the larger of the two segments, representing 65% of sales in 2023.

Before I get to Premium Brands now, let’s go back to Premium Brands in April 2017, the first time the stock was priced in the mid to high $80’s. What was baked into the stock price then, and what is now?

In 2016, Premium Brands had earnings per share of $2.38, its definition of free cash flow of $4.22 per share, $155 million adjusted EBITDA, and return on net assets* of 17.2%. Notably, all of these numbers had shown significant growth over the prior year. Debt was at just 2.4x EBITDA, and while the company didn’t provide hard guidance numbers per se, it did say it expected organic growth to be in its target range of 4-6%, and the company could be expected to make quite a few acquisitions to grow earnings.

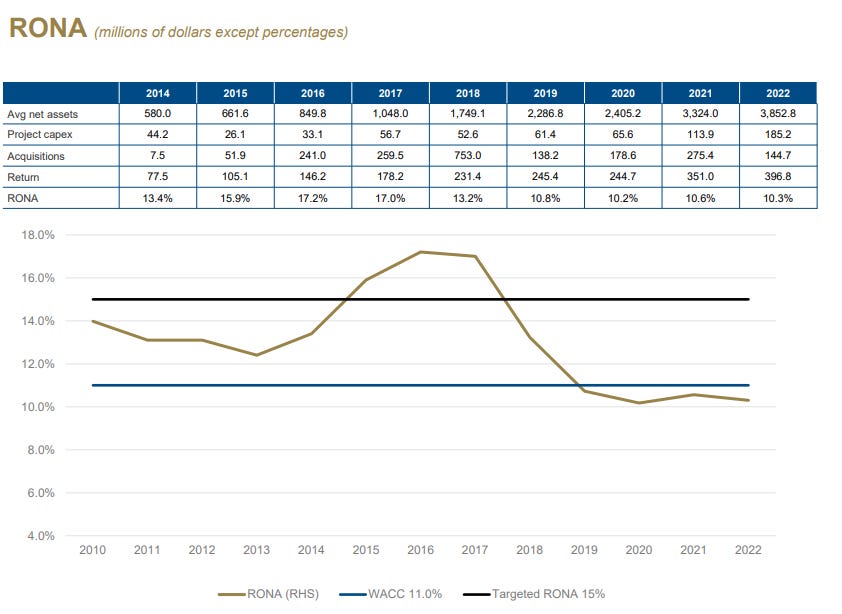

*Premium Brands defines return as adjusted EBITDA less maintenance capex, and net assets as “total assets less deferred income tax assets, accounts payable and accrued liabilities”. You can quibble with this definition being the best measure of returns but the company has used it consistently for years so it does provide an apples to apples comparison over time. And whether it is the best measure or not, higher still is better so I’m going to default to it a lot.

A fast growing company with high returns on capital, a decent balance sheet, with a soaring stock price and a CEO that quotes/often sounds like Warren Buffett. It’s not hard to imagine why the stock was trading over 35x earnings, 20x FCF, and ~19x EV/EBITDA.

The most applicable quote in the MD&A from that time though is this, discussing the company’s return on net assets (RONA).

From 2014 to 2016, RONA improved from 13.4% to 15.9% to 17.2%. 2015 and 2016 offered investors a glimpse that the Premium Brands messaging was true. The company had been making long term investments, and management was good at underwriting those investments. Shareholders had to sit there for years listening to the company say it was investing for the long term ,and this period finally saw those investments bear fruit.

While the stock has done great over its entire history, the majority of the gains came in that period from 2014 to the end of 2017. It just so happens that those years were the years that showed improving or high RONA (2017 was 17%).

What happened after 2017?

2018 - RONA = 13.2%. Explanation:

RONA for 2018 decreased to 13.2% from 17.0% in 2017 primarily due to: (i) business acquisitions made in late 2017 and 2018 that are in the early stages of development and correspondingly are not yet generating the levels of return that are expected over the longer term; and (ii) additional investments recently made by a number of the Company’s legacy businesses in capacity and working capital in order to support future growth.

2019 - RONA = 10.7%. Explanation:

RONA for 2019 decreased to 10.7% from 13.2% in 2018 primarily due to: (i) business acquisitions made during 2018 and 2019 that are in the early stages of development and correspondingly are not yet generating the levels of return that are expected over the longer term; (ii) additional investments recently made by a number of the Company’s businesses in production capacity and net working capital in order to support future growth; and (iii) challenges resulting from a severe outbreak of African Swine Fever (ASF) in China that negatively impacted a number of the Company’s businesses’ operating results and net working capital positions.

2020 - RONA = 10.2%. Explanation:

RONA for each of the last three years has been below its long-term target of 15% primarily due to: (i) business acquisitions and major capital project investments that are in the early stages of development and correspondingly are not yet generating the returns expected over the long term; and (ii) the transitory factors impacting the Company’s adjusted EBITDA.

2021 - RONA = 10.6%. Explanation:

RONA for each of the last three years has been below its long-term target of 15% primarily due to: (i) business acquisitions and major capital project investments that are in the early stages of development and correspondingly are not yet generating the returns expected over the long term – the Company’s investment horizons are generally ten years or longer; and (ii) the transitory COVID-19 pandemic related factors impacting the Company’s adjusted EBITDA.

2022 - RONA = 10.3%. Explanation:

RONA for each of the last three years has been below its long-term target of 15% primarily due to: (i) business acquisitions and major capital project investments that are in the early stages of development and correspondingly are not yet generating the returns expected over the long term – the Company’s investment horizons are generally ten years or longer; and (ii) the transitory COVID-19 pandemic related factors impacting the Company’s adjusted EBITDA.

It must be nice when you can use the exact same explanation as last year.

2023 - RONA = 10.7%. Explanation:

RONA for each of the last three years has been below its long-term target of 15% primarily due to: (i) business acquisitions and major capital project investments that are in the early stages of development and correspondingly are not yet generating the returns expected over the long term – the Company’s investment horizons are generally ten years or longer; and (ii) in 2021, COVID19 pandemic related factors, including significant labor and supply chain disruptions, impacting the Company’s adjusted EBITDA.

Same… but different. For six years now, the company has been claiming that it is not meeting its targeted return because it invests for the long term (10+ years) and in the first few years after a deal is made it is kind of expected to not meet the 15% target. On top of that, there was a year where Asian swine flu affected things, then COVID, then inflation. Six years of “we invest for the long term so returns will improve” is probably a tough pill for investors to swallow. Combine that capitulation with this looking more like a 10-11% company, and it makes sense the stock price is the same as seven years ago. In fact, Premium Brands published this slide, showing that the company acknowledges it has been earning returns below its weighted average cost of capital for four years (now five given 2023’s results).

It’s our job to decide whether we buy this, and therefore can expect returns to improve.

Premium Brands offers a few pieces of information to provide a check of these explanations.

In the three years that RONA was above the company’s target (the only three years in the past 14 years mind you), the specialty food business made up 66%, 61.2%, and 60.7% of revenues.

We can compare that to specialty food being 63% and 65.4% of revenues in 2022 and 2023. Here were the gross margins for both businesses, and the total, for those years:

The proportions of revenue didn’t meaningfully change, specialty foods’ margins didn’t change, and distribution’s margins fell a bit but nowhere near enough to account for this large difference in returns, as the consolidated gross margin percentage was roughly the same over both periods.

How about SG&A?

Not much explanation here either. If anything, we see some cost discipline on the distribution side, reducing SG&A as gross margins went down.

Combine these, and we see that EBITDA margins didn’t change meaningfully:

The numerator of RONA we see isn’t terribly different. What about the denominator?

We can see a general trend up, which indicates that all Premium Brands’ assets have become less productive.

The investment in associates is by far the largest increase, primarily due to Premium Brands’ 2020 acquisition of 50% of Clearwater Seafoods. The investment in associates used to be negligible, but has now grown to a little under 10% of total assets. Interestingly though, the interest earned from investments in associates implies that the return on these investments is actually higher than Premium Brands’ RONA as a whole. That’s perhaps not the most surprising since RONA has been below 15% most years and the Clearwater investment is obviously not responsible for poor results before it was acquired.

I thought I’d find out something more concrete regarding why Premium Brands’ returns were now lower. Simply put, there has been no one thing that has led to this. Inventories have increased a bit vs EBITDA, but not that much. The Clearwater investment has become a large part of net assets, but has actually kept RONA from being even lower. Margins are roughly the same, the proportion of the business that is specialty foods is roughly the same. The lower returns is a pervasive issue.

Premium Brands will almost certainly earn more in the future. The company has published a five year plan…

which it has done several times before. As you can see, the company has successfully hit or exceeded the targets it has set out each time. In discussing the plan, the company has stated it has high visibility on its sales growing to $9.5 billion without any acquisitions, a very impressive 9.6% organic growth rate. I’m confident that Premium Brands will have $1 billion in EBITDA in 2027.

However that organic growth comes with $800 million of capital spending. ~$350 million of that was spent in 2023. If we take Premium Brands at its word that that $800 million of growth capex will lead to ~$350 million of additional EBITDA, it’s hard to argue with the returns.

The question is, will those returns come? We should have a good indication by the end of 2025 whether they are likely to materialize. Since the start of 2021, the company has spent roughly $800 million on growth capex. By the end of 2024, the majority of the projects that this money has been spent on will be completed (many are complete now). By the end of 2025 most of those projects will have had time to stabilize and as such, if returns are going to come, we should see them by then.

The company doesn’t provide RONA until year end, but through the first two quarters of this year, I calculate RONA as being pretty similar to last year. In its most recent conference call, management stated there were several projects and initiatives that had delayed starts, which were expected to be running now that aren’t, so EBITDA was likely to be near the low end of its guidance ($630 million). With that, 2024 RONA will be below 15% again, likely somewhere around 11%.

That is an improvement, can possibly be considered some green shoots.

The last thing I’ll say here is that internal projects/growth capex seems like it will be more common going forward than it has been throughout Premium Brands’ history. As shown above, Premium Brands has spent $3 billion on acquisitions over its history, yet over the period from 2021 to 2027, it is expecting to spend something like $1.3 billion on organic growth, which comes after spending $1.7 billion on capital projects between 2017 and 2021. Paleologou has stated he sees a lack of industry capacity for the company’s products, so increasing capacity is a worthwhile use of capital.

While Premium Brands has spent a lot of capital on its own facilities, the market has come to expect acquisitions, and likely considers acquisitions more within the company’s circle of competence. It also will take longer for capital spending to result in returns (acquisitions contribute more or less right away, a new production facility for example does not). A little more faith in management will be necessary.

In 2017 you were paying those high valuations for Premium Brands while it was earning what would turn out to be cyclically high returns on its assets. You didn’t know that at the time, but given the company had a target of 15%, the best case was likely returns staying roughly the same. And to be fair, paying 35x earnings and 20x free cash flow wouldn’t have been all that crazy if it had continued earning 15% RONA.

Today Premium Brands can be purchased for ~30x earnings (~22x adjusted earnings, some of the adjustments make sense, some don’t, so you could probably split the difference and call it 26-30x earnings), 14x free cash flow, and 9x EV/EBITDA.

If Premium Brands is about to embark on a run of increasing returns on net assets, these valuations could prove to be attractive. A company growing like Premium Brands is, earning improving mid-teens returns on net assets/capital, I could see it trade at a higher multiple. The P/E seems high, but the free cash flow and EV/EBITDA multiples do not.

On the free cash flow number, I should mention something before taking it at face value.

Adding back acquisition transaction costs is something a lot of companies do. I wish they wouldn’t, as they are real costs, but I get the argument that they are related to growth, and because it’s so widespread, I’ll give it to them. The plant start-up and restructuring costs, again, I get the growth argument. I buy it less but I get it.

The maintenance capex is the real outlier here. You can see that for the first two quarters of 2023 and 2024, maintenance capex was $25.6 million and $23 million respectively. This is considerably lower than depreciation of capital assets in those two periods of $41.3 million and $47.9 million, respectively. For the full year 2024, management has guided maintenance capex to be in the range of $50-$55 million, again, materially different than depreciation which is likely to be pretty close to $100 million.

I’m not saying that management is hiding anything, or intentionally misleading investors. But I do think that quite a bit of maintenance capex gets classified under the growth capex umbrella. The company describes one of its growth projects as this:

A new 67,000 square foot sandwich production facility in Edmonton, AB, which will replace an existing 23,000 square foot sandwich production facility in Edmonton, AB

Nobody is going to argue that isn’t a growth project. But maintenance capex by definition is the capex needed to maintain current sales. If you are building a 67,000 sq.ft factory to replace a 23,000 sq.ft one, 1) you almost certainly aren’t maintaining the smaller factory you’re going to replace in the meantime, and 2) quite a bit of your new larger factory will simply be needed to maintain your old production amount. Yes, your new facility is going to allow higher sales, but if your current sales could be maintained in 10,000 sq.ft of the new facility (estimating for higher efficiency, ie. sales per sq.ft), wouldn’t ~1/6th of the new factory kind of be akin to maintenance capex? It’s being built at the expense of maintaining the old factory.

Multiply that idea across many projects each year and I bet that the maintenance capex number gets closer to depreciation. If you make that adjustment to free cash flow, using depreciation instead of the disclosed maintenance capex.

Remember that the numerator of Premium Brands’ RONA calculation is adjusted EBITDA - maintenance capex, so if you consider maintenance capex understated, you likely also think RONA, underwhelming as it is at around 10-11%, is overstated.

Balance Sheet and Convertible Debentures

Over the next 3 years, Premium Brands has plans to spend something like $300 million on internal growth projects. Free cash flow, as defined by the company, I expect to be something like $280 million in 2024. The current dividend eats up ~$150 million of that. That leaves just $30-$50 million of excess free cash flow each year after paying the dividend and growth capex for M&A. This assumes some growth in FCF each year, which I expect a lot of which will go to dividend increases.

If Premium Brands can maintain/grow free cash flow a little, it has the free cash flow to meet its growth targets. And if the company hits those growth targets, without increasing debt too much (which it doesn’t need to given the free cash flow), leverage will come down naturally and come down to its target or below.

The balance sheet is strained right now, and that will hamper management somewhat, but if they can meet the targets they’re aiming for, they should be able to grow into their debt. You have to believe in the returns management say are going to come, their ability to perform M&A, and their desire to be within their targeted leverage range (you can see they are fairly often above it), but it seems plausible the current debt isn’t a huge red flag.

Premium Brands has been a prolific user of convertible debentures, and has the interesting view that the convertible debentures are an “equity strategy”. Considering that the company, I believe has more or less settled every debenture it has issued through conversion, it makes sense. And if the idea is to grow through issuing equity anyway, the convertible debenture makes a lot of sense. If the debentures get converted, you are raising equity at a large premium to the stock price when you need the money (Premium Brands has managed a 65% average premium over its many issuances) in exchange for a few years of relatively modest interest payments. The convertible debentures have no interim principal payments, no covenants, and often don’t require cash at maturity. It makes a lot of sense.

That said, right now the company has three issues of debenture outstanding:

The first maturity coming up is in April 2025. $172.5 million with a conversion price over 100% higher than today’s stock price. That one will have to be settled in cash, which likely means issuing another series of debentures. It’s by no means safe to assume either of the other issues will be able to be converted either - getting to those conversion prices would imply total shareholder returns of 20+% and 15+% respectively.

The convertible debentures still have a lot of features, but it looks like the magical era of always settling the debentures by converting to shares is over, and refinancing the debentures will be a new hurdle for management to overcome (though it shouldn’t be hard).

Conclusion

I got so excited about Premium Brands at first when I had looked at nothing but the stock chart (compounder for many years and then flat for seven years) and reading the CEO’s letters. That’s why you got to put in the work. After looking at its history of not meeting return targets, the relatively modest returns on capital/net assets, the large amount of capital it is spending (with reason to doubt the returns on those projects), I lost a lot of that enthusiasm. Then I looked at the valuation, and with the exception of on EV/EBITDA, Premium Brands Holdings doesn’t even look particularly cheap.

I can envision being wrong about it. I can see a world where RONA goes higher as the capital projects it is doing come online and perform. Where the big growth the company is guiding comes at good returns, and leads to both more free cash flow and increasing RONA. Conservatively assuming slightly lower EBITDA to free cash flow conversion in 2027, Premium Brands could be earning close to $9 in its definition of free cash flow at that point, or even a bit under $8 if you use an estimate of depreciation instead of maintenance capex. 15x FCF (the multiple the market applies to the stock now while it is relatively pessimistic) at that point would lead to a stock price of $120-$135. If returns improve, maybe the stock could trade up to 17x or 20x or whatever. Owning shares looks pretty appealing in that world.

For me, that’s just a bridge too far. I like the idea of buying a beaten down compounder facing temporary troubles. I like the idea of owning a company raising its dividend by 10% each year with modest payout ratios while still financing a lot of internal growth. I like investing in a management team that thinks about their company like Paleogelou and co. do (or at least how they speak). But the valuation does not seem low enough to justify the relative uncertainty of the returns of how good the business is. I will be following the company and its results. Like I said, by the end of 2025, it should be fairly obvious whether RONA is improving or ever going to improve. If you’re on the ball, you should be able to catch improvement sooner. Because Premium Brands Holdings has the appealing aspects I mentioned, if I catch wind of improvements in the future, and the price is in the ballpark it is today, I could see myself buying the stock. For now I’m just an interested observer though.

The projection of $9 in free cash flow (FCF) for Premium Brands in 2027 could be optimistic if the assumptions about EBITDA and capital expenditure (CapEx) are too generous. If depreciation is higher than expected or if maintenance CapEx proves to be more than projected, the FCF might fall below expectations. Additionally, changes in market conditions, such as rising costs or declining revenue, could further erode profitability, making the $9 target harder to achieve. A conservative estimate of FCF should account for these potential risks.

Great post! I appreciate your thorough explanation and your use of quotes from the company's letter. It is a challenging topic, and in the “commodity industry,” offering promising returns without a concrete plan can be daunting