After this last post about Morguard Corp looking closer than ever to acquiring Morguard REIT, it seems a good time to republish this post about Rai Sahi, the founder and CEO of Morguard. Sahi has been written about before, but as far as I can tell this post of mine was the most comprehensive thing written about him aand his history. At the very least, it does a good job of compiling a lot of sources across the internet. Morguard gets little attention these days despite having almost $20 billion in assets under management, making it one of the largest owners of real estate in this country. That’s a shame, because what Rai Sahi has done to grow Morguard to this point is very impressive. As with mpost of these reposts, the numbers are a bit outdated, and Morguard’s performance numbers since late 2019 hurt some of the performance charts I highlight in the post, but I don’t think that rough three years negates the long track record Sahi has, nor do I think the lessons one can learn from him are no longer valid.

I hope you enjoy reading about him as much as I did/do.

Rai Sahi moved to Montreal in 1971, and after working a series of odd jobs, began selling life insurance door to door in Kingston, Ontario, the job he credits with honing his English and people skills. He eventually moved to Toronto and got a job in commercial real estate lending with BMO. This position taught him how to value a business, how to evaluate risks, and put him in front of a lot of ambitious entrepreneurs. After a while, he realized he could do what they were doing, and the experience led to the next phase of his career – the start of his corporate “raiding”.

He bought Advanced Extrusions (which manufactured toothpaste tubes and aerosol cans) in 1981, with partners, for $7 million (7x P/E). While there the new owners purchased equipment to boost productivity, doubled revenue, and managed to sell the company to CCL Industries for $22 million in 1985.

He used the proceeds from that sale to buy two trucking companies and combined them to create CF Kingsway. It was Canada’s third largest trucker by the time it was sold in 1988 for $70 million. Prior to selling it, he bought out his partners.

As part of the CF Kingsway deal, Sahi received a board seat and shares of the acquirer, Federal Industries (a sprawling conglomerate run by Jack Fraser). After various disagreements Sahi resigned from the board, then acquired 8% of the company, got Federal to focus on its metal business – thereby becoming Russell Metals – and in 1997 waged and won a proxy fight to force out Fraser and the CEO while getting a board seat back again. He sold his Russell stock later that year.

The Federal/Russell saga is secondary to the defining Sahi investment of the 90’s.

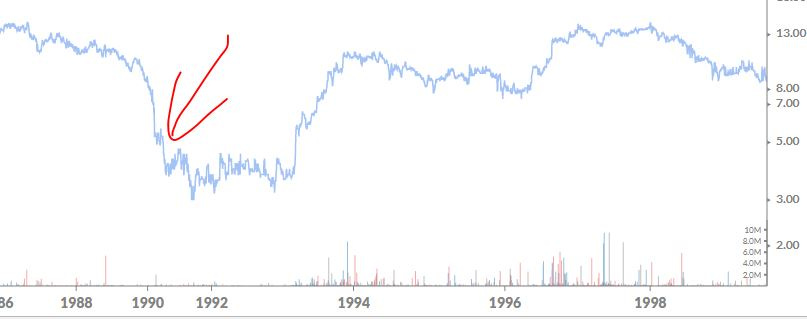

In 1990, Sahi bought 23% of Acklands, which had been in the dumps for a couple years at that point. The red arrow points to approximately when Sahi bought his stake, and he became CEO towards the end of 1990; what the chart does afterwards should speak to Sahi’s value creation.

I’d call it semi-hostile. Management certainly didn’t want it, but the pension funds that were invested in Acklands were pleased to have me.

– Rai Sahi

Once he got control, he completed 33 acquisitions and tripled revenues over five years. In 1996 he started selling off assets and spinning off companies.

Sahi got his start investing in real estate in 1997, purchasing 40% of Goldlist’s IPO, and changed the name of the company to Acktion Corporation to reflect the company’s expanded focus. Acktion invested in a few more real estate companies, including a stake in Morguard REIT in 1997 and acquiring all of Morguard Investments Limited in 1998.

In 1999, Acktion’s ownership of Morguard REIT went over 50% when Sahi sold some of its wholly owned real estate (properties it acquired by acquiring Devan Properties) to the REIT. Sahi also obtained control of Goldlist, upping Acktion’s stake to 66%. That year he cleaned up the last remnants of Acklands, and Acktion entered 2000 as a pure real estate company with a little over $1 billion in assets.

In the early 2000’s Sahi consolidated control of the various real estate companies he owned stakes in, and in 2002 he changed Acktion’s name to Morguard Corporation.

Sahi took an underperforming industrial supplies and auto parts distributor (Acklands had three presidents and lost $33 million in the three years before he got there), sold what he could, and turned it into a box of cash with which he began a real estate company.

From there, he went on to mould Morguard into what it is today – a real estate owner and manager with over $21 billion of assets under management. We’ll get back to the hows of building it in a bit, because I want to tell you about Rai Sahi’s other empire.

TWC Enterprises

Tri-White Corp was a holding company spun off from Russell Metals, the most valuable asset of which was a tourist railway in the Yukon and Alaska.

Sahi ended up acquiring over 70% of Tri-White, and then went to work. He sold off most of the assets, with the notable exception of the railway, and after cleaning things up he had Tri-White in a position to take advantage of a rare opportunity when it came along. I won’t be able to explain it any better than this article, so I will quote it directly.

The chance came just before Labour Day weekend in 2001. At the time, the largest stake in ClubLink was owned by the world’s leading golf course and resort owner, Dallas-based ClubCorp USA Inc. On the Thursday before Labour Day, ClubCorp’s chief operating officer, James Hinckley, called Sahi at home. Would Sahi be interested in buying ClubCorp’s stake in ClubLink?

At $7 a share, it would be a $35-million transaction. Sahi wasn’t game, but the ClubCorp executive had the persistence of a motivated seller. Having expanded rapidly, ClubCorp found itself in a sudden equity crunch. It needed to offload its Canadian stake by Tuesday, only four days later, or face an uncomfortable rendezvous with a lender. So the price was flexible.

“My senior management unanimously were against the deal,” Sahi recalls. When Hinckley followed up on Tuesday at about 11:30 a.m., with only hours to go before the deal’s deadline, Sahi surrendered to an impulse.

“I really don’t want to do this deal,” Sahi said, “but I’ll give you a number-we’ll buy five million shares at $5 each.”

The deal valued the stock block at $25 million- a whopping $10 million less than the asking price. Hinckley gulped and accepted on the condition that Sahi get the money to ClubCorp by 4 p.m. Considering the stock had been trading at a few cents above $6, the deal was a bargain. And it made Sahi into ClubLink’s largest shareholder, with 25.1% of the company.

For what it’s worth, Sahi’s memory seems to differ slightly in his retelling for this more recent article:

ClubCorp was facing a deadline with a lender in just three days, and it desperately needed cash. Hinckley and Simmonds wanted Sahi to buy ClubCorp.’s 25.1% stake at $7 a share, for a total of $35 million. Sahi heard them out, nodded, then offered them not $7, but $5 a share, for a total of $25 million. They said they needed to think about it. On Monday, the day before the deadline, they caved—they had no choice.

The point is the same: Sahi saw a motivated/desperate seller, and “negotiated” a wonderful price – almost 20% below the market price.

What is more impressive than the price though, and what I find fascinating, is the speed he could do the deal. This was a huge acquisition – like half of Tri-White’s market cap at the time. And he did the deal over a weekend. Here is what Sahi said about his rationale at the time:

“I didn’t have a lot of time to think about it, actually, because that first deal was done over a weekend. The only thing I knew was that I was in the real estate business, and these guys have got 10,000 acres of land, which may be worth something.”

How awesome is that? To tie this back to my first Canadian Outsider Jonathan Goodman, it’s a bit like Goodman taking the priority review voucher with him to Knight from Paladin without knowing what it might be worth, just that it was valuable.

Sahi definitely had more justification for the deal and knew he didn’t need to do too much research because he could always slowly unload shares at the market price, but I have a thing for stories of people doing deals having done only “napkin math”, so I love this story.

In late 2002, Sahi issued a hostile bid for the rest of Clublink. A holding company called Southwest Sun came in and outbid him for a 16% stake, but the move scored Sahi the position of co-chairman of the board.

Sahi played the good soldier (partly because of a standstill agreement between Southwest Sun, the other co-chair (eventual CEO Robert Poile), and Sahi) until Southwest Sun, Poile, and others agreed to pool their shares for voting purposes, giving them 39% of the votes. Rai took this as a declaration of war and decided to buy them out, offering $13.25 (a mere $0.40 premium over the current share price) for their block of shares. The dissident shareholders accepted, and Tri-White gained control of Clublink.

Tri-White bought the ~30% of Clublink it didn’t already own in 2009, issuing 1.1 shares of Tri-White to Clublink shareholders, therefore paying somewhere around $5.28 for the last Clublink shares (based on Tri-White shares being in the $4.80 range when it announced the deal).

The company name was changed from Tri-White to Clublink, and more recently to TWC Enterprises.

Sahi’s dealing to acquire Clublink shows a lot about him.

It shows his “raidering”. He raised a stink and made a hostile bid for the company about one year after buying his initial shares. He questioned the competency of management (including the CEO Bruce Simmonds who first hooked him up with ClubCorp to buy their shares!) as well as their motives. The fight for Clublink was a tough one and Rai came out on top.

It shows his savvy. As he put it above, Clublink owned 10,000 acres of land, including a lot of very valuable land in the GTA. All told he paid:

$25 million for his first 25%

$88 million for the next 39% (which he thought he overpaid for, saying “[they] wouldn’t sell to me unless they got a good premium. But an extra $10 million was probably worth it in the long term.”)

$24 million for the last ~28%

There’s another 8% unaccounted for. I can’t find purchase prices for these shares, but I think it’s safe to say he didn’t spend more than $50 million for them.

He paid less than $200 million for 10,000 acres of land, less than $20,000 an acre. And this land makes him a profit every year due to the profitable golf operations. Glen Abbey, a 229 acre course in Oakville, is likely worth more today than Sahi paid for all of Clublink.

Sahi acquired more golf courses for Clublink, including expanding to Florida, but at the same time was working on redeveloping some courses.

He put the Highland Gate course in Aurora, ON into a JV with a developer, thereby owning 50% of a project with a planned 159 SFHs and 114 apartments. He is currently battling with the towns of Oakville and Ottawa about his plans to develop Glen Abbey and Kanata, respectively. And he is working with developers on plans for one of TWC’s courses in Florida.

In 2018 he sold White Pass, the Yukon/Alaska railway, to Carnival Corp for $359 million and chose to take $25.9 million of the purchase price in Carnival shares. Since then, Sahi has used TWC to purchase 14% of Automotive Properties REIT, and the two cases of acquiring shares in other publicly held companies shows he’s moving to make TWC a holding company meant for anything and everything undervalued (which was the reason for changing the name of company to TWC from Clublink in the first place).

How did Rai Sahi build these two great companies and so much wealth for shareholders who trusted him? The strategies won’t be too surprising to those familiar with the Outsiders, but Sahi has done things unconventionally from many others.

Hostile Takeovers and Activist Investing

Sahi claims that he has done more hostile takeovers than anyone else in Canada, and there’s no reason not to believe him. As described above, both Morguard and TWC were built on hostile takeovers, and he even got the Morguard name through one.

I was never hostile to shareholders, I was only hostile to incompetent management

– Rai Sahi

I’m in agreement with Rai here. He wasn’t doing Brookfield-like takeunders. He targeted underperforming companies or undervalued assets, and then created a bunch of value for shareholders. Know how he said his purchase of Acklands was semi-hostile because management didn’t go for it? I recently found Acklands’ 1996 annual report, six years into his turnaround.

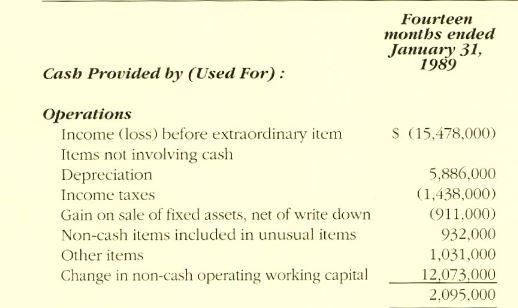

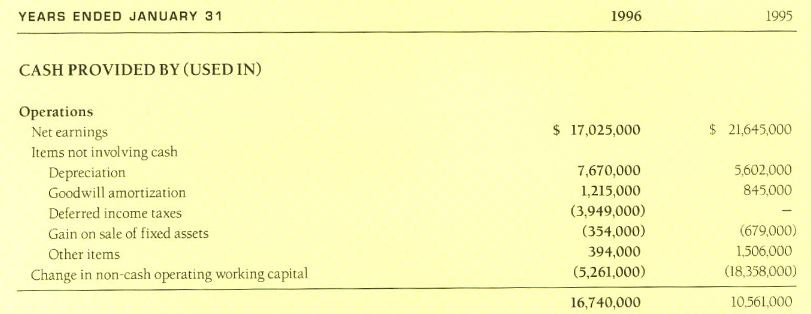

The graph spells it out nicely, but now check out the cash flow statements from 1988 (the most recent annual report I could find from the pre-Sahi era) and 1996:

Who, besides old guard management protecting their jobs, would consider Rai taking over the company “hostile” with results like this? Importantly, the results of his turnaround also appear on the stock chart, you can see in the chart at the top of this post the stock was in a one way elevator down before Rai got there.

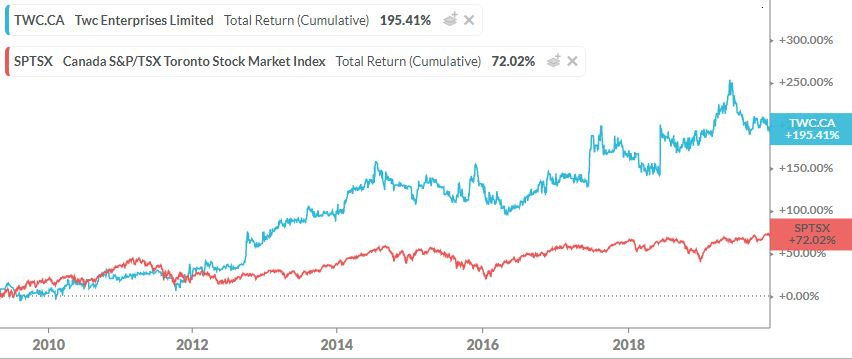

The same can be seen at Clublink. Minority shareholders got bought out at a pretty low price for their shares, but they received TWC shares as their compensation. Here’s how that investment has done since that day:

And while the method can be called “hostile”, all it really amounts to is Sahi running companies in a way that boosts value for shareholders. He was finding companies not being run for shareholders, and redirecting the focus so everyone benefited except for incompetent managers. Shareholders were always better off after Rai got involved and that seems like the opposite of hostile.

Buying Pieces of Companies

This is something straight outta Henry Singleton’s playbook.

It is very rare to see, particularly in real estate, companies investing in stock of other companies in their industry, but Sahi has done it countless times. Of course Morguard got its start in real estate by buying stock in a real estate company’s IPO, for a while that’s how its real estate business was built. By investing in stock, rather than doing immediate outright acquisitions, Sahi avoids paying a premium on all shares. He can get close to management, who likely feel pressure to be more shareholder friendly given his reputation.

Rai’s initial foray into a stock is usually the beginning of a slow moving takeover. For instance, he bought his first stake (20%) of Revenue Properties in 1997, and slowly increased its position for almost 11 years, before finally bidding for the last of the outstanding shares, at which point Morguard owned over 72% of Revenue Properties.

He did it with Goldlist, Morguard REIT, Acanthus, Temple Hotels (just recently bought out completely), etc. He used the playbook over and over again to avoid, as much as he could, paying premiums over market prices, and this allowed him to opportunistically buy larger stakes when it made sense for him. I used the example of Revenue Properties above – don’t you think it made a lot of sense to bid for the whole company in the summer of 2008?

He had the capital available because he only had to bid for 28% of the company, and he was able to make the investment at the point of peak pessimism.

We can see two current examples of Sahi doing this exact thing, one each at Morguard and TWC.

Morguard recently announced that it has acquired almost 15% of Plaza Retail REIT. He explained his rationale to Andrew Willis of The Globe & Mail:

In an e-mail, Morguard’s CEO said the Plaza units “were acquired for investment purposes, at a price we believe to be below their fair value.” Morguard disclosed it most recently snapped up Plaza units for $4.20 each. By RBC Dominion’s calculation, the company’s book value is $4.64 a unit. Plaza units closed on Friday at $4.44 on the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Mr. Sahi went on to say that there was a strategic rationale behind the purchase. Morguard’s CEO pointed out that Plaza’s holdings in Eastern Canada dovetail neatly with his company’s existing portfolio, which is concentrated on Ontario, Alberta and the United States, and is weighted more to residential and office buildings than retail properties.

As with many of his investments, Mr. Sahi’s initial approach is to remain a supportive passive investor, even though Morguard is now Plaza’s largest single-unit holder. He said, “The Plaza management team is successfully executing on a business plan to strengthen its portfolio every year, as it continues to pursue opportunistic acquisitions, as well as strategic leasing and redevelopment opportunities.”

There’s a good chance that Morguard doesn’t acquire anymore of Plaza if the unit price is consistently near whatever Rai decides fair value is. But as the name of that G&M article alludes to, should there be a broad decline in public REIT prices, we can be pretty sure that Sahi will be out for more.

Debt

We’re probably one of the lowest leveraged companies in real estate.

– Rai Sahi

Morguard, for the last little while, has had debt-to-assets of around 40%. Without too much fact checking, that doesn’t appear to be uncommonly low (Canada’s two largest REITs, CAR.UN and REI.UN, are both around there as well), but he’s not wrong in saying Morguard doesn’t use a lot of leverage.

What he does do uniquely is make sure Morguard never faces a wall of maturities that can threaten the company. Sahi has typically structured Morguard’s debt so that only 10% of it matures each year, borrowing with ten year terms as much as possible.

That means we have 10 per cent of our debt coming due every year so we should be able to absorb rising rates if they don’t go up too rapidly.

– Rai Sahi

As he says, this helps to insulate Morguard from a rising rate environment (it would take 10 years for the full effect of rate increases to hit the company), but it also means that Morguard should never find itself in any sort of liquidity crunch. Morguard survived the great recession with relative ease, and Sahi attributes much of it to this rule. Here’s an excerpt from a great Sahi profile explaining what it was like at that time just after Lehman Brothers collapsed:

As soon as he got into the office, he jumped on the phone and started calling banks, life insurers and other lenders. His heart sank: They had all stopped rolling over mortgages for even their favourite real estate clients, effective immediately. “One investment bank went under, and the whole world collapsed,” Sahi recalls. “I was worried the real estate business was going to come to an end.”

Over the next several weeks, Morguard’s share price got pounded. By November, it had plummeted from $30 to less than $16. It stayed down until the bottom of the financial crisis the following March. But Morguard survived—thanks to a bit of luck. The company had a history of staggering the maturity of its mortgages, so it only has to roll over about 10% of them each year. In late 2008 and early 2009, it only had one significant loan come due: $10-million worth of mortgage-backed securities, an amount it could cover from its own cash flow.

That continues to this day – Morguard has roughly $5.5 billion of debt – and there’s somewhere between $400 million and $600 million maturing each year for the next several years.

Sahi is unlikely to ever find himself forced to sell when he doesn’t want to, and in times when values disconnect from prices, he’ll be one of the ones most able to take advantage.

Long Term Thinking

Rai Sahi is a notoriously long term thinker. Here’s a story from that same Sahi profile, about The Heathview apartments:

The property was acquired for a song back in 1997, when Morguard swooped in to take a large stake in a struggling apartment developer and landlord called Goldlist Properties Inc. Then Sahi patiently sat on it for years as it increased in value, taking his time while haggling with city and provincial officials to get The Heathview project approved. The buildings didn’t open until late in 2014.

The most telling aspect of the project is that it’s not another condo development—despite the sizzling market and its tony Forest Hill address. Instead, Sahi built rental buildings that he will continue to own, while collecting his monthly rent cheques, probably until the end of time. And why not a condo? Why not go for the instant windfall, rather than a trickle of income for years to come?

When I ask him this, Sahi peers at me for a moment in the most unnerving way. Then he fires back his answer in a deep and gravelly voice. Condo developers “are a lot of speculators,” he says, who borrow heavily to make risky bets. In a soaring market, they can make out like bandits. But when the market downturn hits—and it will—they tend to get wiped out. “We’ve seen that movie a few times in the past 30 years,” he tells me with a cheeky grin.

He clearly is not concerned about the share price next quarter or next year.

I’m never worried about the share price, analysts tell me I’m the only CEO who ever says they’re overvaluing the stock.

– Rai Sahi

And of course, Clublink. He knew there was a tonne of value in the land, but the value of land that is currently in use and not zoned for development is obviously not realized for years or decades. No problem for Rai. The value of Clublink still hasn’t been realized, thirteen years later.

There is long-term value in this company. But you need to have patience.

– Rai Sahi

Capital Allocation

Rai Sahi has used his shares as currency, at both companies.

He issued shares of Tri-White to purchase the last of Clublink. The decision to issue Tri-White shares in 2009 would have probably bothered me if I was a shareholder, but of course whether it was a good decision or not depends on if Clublink was more or less undervalued than Tri-White at the time. Given how much value is in Clublink’s land, isn’t recognized by the market now and surely wasn’t in 2009, I’m inclined to believe Clublink was more undervalued. But there’s another wrinkle to the equation.

As part of the process and in accordance with applicable regulatory requirements, CCC has delivered a formal valuation to the Special Committee that determined the fair market value of the ClubLink Shares, as at May 29, 2009, to be in the range of $6.69 to $9.73 per share and the fair market value of the Tri-White Shares to be received by ClubLink shareholders, pursuant to the amalgamation, to be in the range of $7.08 to $8.74. CCC has also provided its opinion that, as at May 29, 2009, the consideration to be paid to ClubLink shareholders, other than Tri-White and its affiliates, is fair from a financial point of view.

Sahi was able to issue shares on the basis of their “fair value”. Given he was able to issue his shares based on a value far above their market price, it seems clear to me it was a good decision (that fair value estimate of Clublink shares certainly doesn’t fully account for the land value).

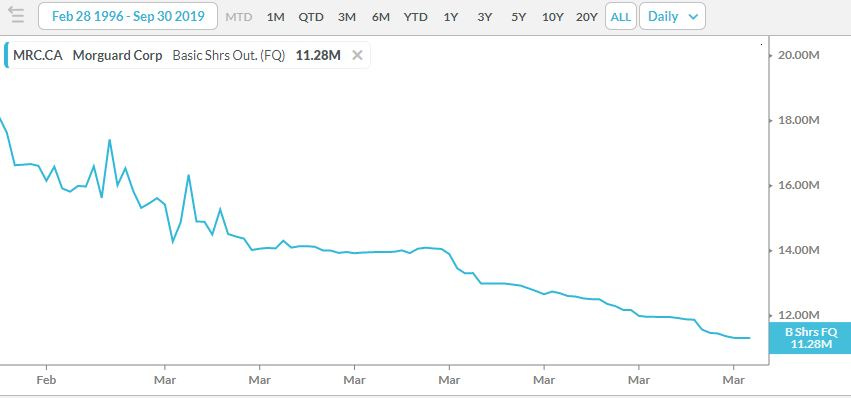

While Sahi used shares on occasion to acquire companies for Morguard, Morguard’s share count over time makes it clear what his priority is.

I could talk a bit about his real estate decisions, but honestly there aren’t too many case studies out there with numbers to show so I’ll let the book value and EBITDA growth at Morguard speak for itself. At year end 1997, Morguard’s book value was $21.16 per share. Today it’s roughly $325 per share. Since pivoting to real estate, Sahi has grown book value per share by 13.2% per year*. 1997 EBITDA was $13.7 million, in 2019 it will be over $300 million (non-consolidated).

*The period includes the IFRS change in 2011 which changedin how Morguard values its investment properties on the balance sheet (values went up), but I think the value creation still holds.

I will speak broadly about Sahi’s real estate choices, because I think they do speak to his skill even if they don’t say as much as his track record of results.

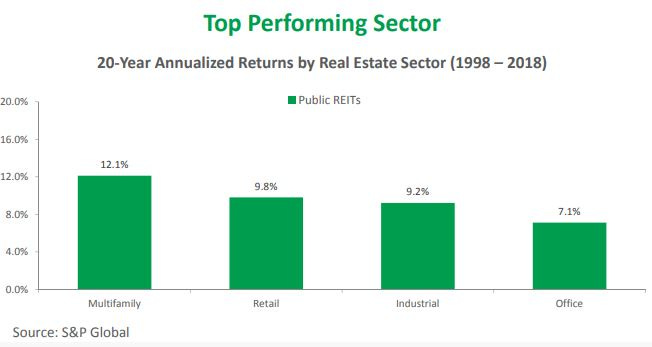

Sahi first got involved in real estate by buying Goldlist, a portfolio of multifamily properties – he was investing in apartments years before it caught on as everyone’s favourite sector.

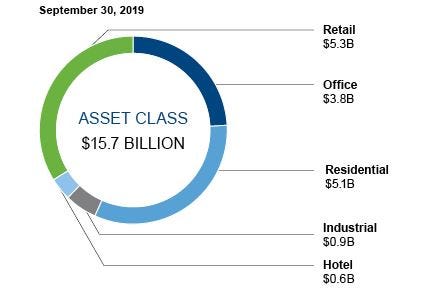

Now, Morguard is diversified across essentially all real estate sectors.

We know how beaten down retail real estate is right now, and in spite of that it was still one of the best performing RE sectors over the best 20 years. There’s little reason to think multi-family residential won’t continue to perform well. Morguard’s office properties are mostly located in the GTA and Ottawa, as are the industrial properties.

The hotel properties are a relatively new addition (Morguard is just about to fully acquire Temple Hotels, another slow moving takeover by Sahi), but hotels are selling for more than their IFRS values, and they also offer a cheap way to acquire land for redevelopment.

As for dividends, both Morguard and TWC pay minuscule yields (0.30% and 0.60% respectively). The two Morguard REITs pay hearty dividends of course, but little can be read into that since they are mandated to pay out a certain amount.

Sahi has made the decision, correctly, that he can allocate capital better than shareholders; instead of paying dividends, he buys back shares, or buys more Morguard REIT (MRT.UN) or Morguard Residential REIT (MRG.UN), or buys other publicly traded real estate (eg. Temple Hotels and Plaza REIT), or reinvests by buying more real estate or redeveloping the properties Morguard already owns.

REITs

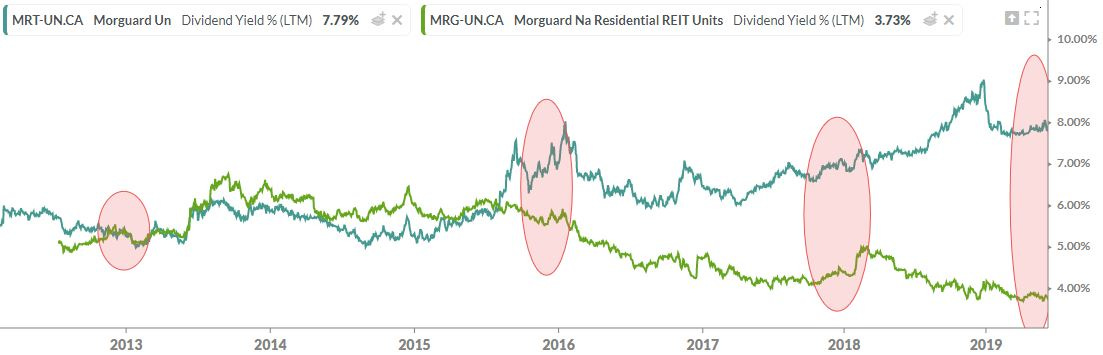

By having publicly traded REITs, Sahi has the somewhat unique tool of being able to conduct “buybacks” of the REITs, as well as being able to issue shares of the REITs when they are valued expensively to raise capital without diluting shareholders of the parent company. And the differing values of MRT.UN and MRG.UN have presented opportunities for Morguard to fluctuate its ownership of each depending on where the best value is.

I realize a REIT’s yield isn’t the best indicator of its value, but I think it does a pretty good job in this case, and the comparison shows how the valuations of Morguard’s REITs have diverged, especially when combined with the chart of the unit prices.

I highlighted four periods on the charts:

At the end of 2012, the year of Morguard Residential REIT’s IPO, Morguard owned 57.1% of it and 42.9% of Morguard REIT.

At the end of 2015, Morguard owned 48.7% of MRG.UN and 50.4% of MRT.UN.

At the end of 2018, Morguard owned 46.9% of MRG.UN and 57.6% of MRT.UN

As of September 30th, 2019, Morguard owned 44.8%of MRG.UN and 58.1% of MRT.UN.

Morguard reduced its ownership of MRG.UN not by selling any but by issuing units of MRG.UN and not buying a proportional amount of the issue. Sahi didn’t want cash for Morguard, he simply saw opportunities to raise money from outside investors, and the end result is more fees to Morguard – Morguard’s fees from the REITs are determined by their gross book value and FFO, so issuing shares above book value is in MRC’s best interest.

Skin in the Game

Rai Sahi personifies skin in the game. He owns almost 60% of Morguard, almost 70% of TWC, and owns stakes in the REITs as well. He is the consummate owner-operator.

Conclusion

Rai Sahi is a true rags-to-riches story. He came to Canada with nothing, and took any work he could get. He worked hard, received his CGA accounting designation, went to BMO where he worked his way up until he realized the ones he was lending money to were the ones making the real money and he decided he could be an entrepreneur too. Since then he has succeeded at everything he’s done. He turned around a manufacturer, a trucking company, an auto parts and industrial supply distributor, and now has built one of Canada’s largest real estate companies, managing over $20 billion of real estate.

Sahi has done it his own way. He runs two of the least promotional companies in Canada. He pays out a nominal dividend in a sector known for yield hungry investors. He usually buys companies slowly over time instead of paying a premium on all shares at once. And when he chooses to return cash to shareholders, he does so by buying back shares.

Since the start of 1991, his first full year trying to shape the company, Acklands/Acktion/Morguard has returned over 4000%, or just a touch below 14% annually. The performance is really put in perspective when compared to the return of the TSX and TSX Real Estate Index (note the performance for this index doesn’t go back to 1991):

Returns at TWC haven’t been as strong, being just north of 10% since completing the acquisition of Clublink, but Sahi also hasn’t got to implement his plan to create value there yet. TWC has still lapped the TSX and then some:

Shareholders who have trusted Rai Sahi as steward of their capital have been greatly rewarded, and he has done so in what is unfortunately an unorthodox way. If anybody can be considered a Canadian Outsider CEO, it’s Rai Sahi.

An excellent summary/ storey. I’ve been on this ride with him for awhile now!!