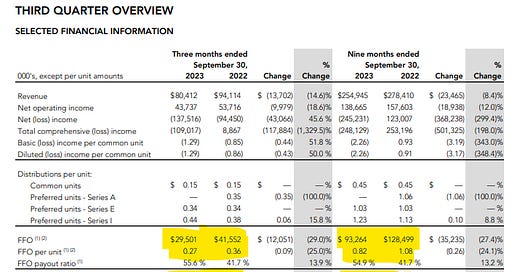

I was reading a tweet thread the other day regarding Artis REIT, and one of the replies was from a smart guy, who I know knows REITs well (he follows me after all!), questioning why Artis REIT’s FFO (funds from operations) was so different from its AFFO (adjusted funds from operations).

In the quarter that was being referenced, AFFO was over 40% lower than FFO, and while that was larger than the difference the year before, both years (and both years through nine months) showed a considerable difference.

I wasn’t sure if that was an unusually high difference compared to other REITs, but it seemed pretty high.

I decided then that I hadn’t written in a while and that the question of FFO vs AFFO would be as good as anything to write about. Admittedly “as good as anything” does not mean interesting, since I’m positive that most people reading this had their eyes glaze over just now. You always have my permission to stop reading, and you of course don’t require my permission, but I can’t emphasize enough how unoffended I’ll be if you stop reading now.

When I originally took a deep dive into Morguard REIT (which I wrote about here though I’m not referencing this post), I got pretty into the weeds with how it was calculating its cap rates and its AFFO.

During that research, I ended up finding and reading the REALPAC Funds From Operations (FFO) & Adjusted Funds From Operations (AFFO) for IFRS white paper. This clearly, and succinctly, explains how companies/REITs are to calculate and report FFO and AFFO.

FFO

I think most people, for the most part, understand FFO. You’ll still see something like this every once in a while…

but most people get the basic adjustments to get from net income to FFO, and the purpose of FFO. REALPAC lists 21 adjustments to get from net income to FFO, but a couple of examples will show you the biggest drivers.

Here is CAPREIT’s 2022 FFO reconciliation:

Fair value gains and losses on properties, investments, and financial instruments.

Here is Dream Office REIT’s Q2 2023 report:

Fair value adjustments and the net income from an investment of its investment in Dream Industrial REIT.

Plaza REIT’s 2022 annual report:

Fair value changes.

As you can see, and I think you likely intuited this anyway, fair value adjustments make up the biggest difference between net income and FFO usually. For REITs, the majority of those fair value adjustments will be related to their properties, but we can see that other instruments can swing net income too.

The Purpose of FFO

This is copied straight from the white paper, with some parts omitted for brevity:

In particular, financial statements prepared in accordance with IFRS do not provide stakeholders with the most relevant information on the performance of the underlying property portfolio under management. Unrealized changes in fair value of real estate property, historical cost depreciation of depreciable real estate properties, gains or losses on disposals of properties and other non-cash items do not necessarily provide an accurate picture of the company’s past or recurring performance. For this reason, comparisons of the operating results of reporting issuers that rely solely on profit or loss have been less than satisfactory.

REALPAC has adopted the term FFO so it can be used as a supplemental measure of operating performance for the industry. In particular, it was hoped that prices of various reporting issuers’ stocks could be compared with each other and in terms of the relationship between stock prices and FFO. Thus, the original intent was that FFO be used for the sake of determining a supplemental capitalization multiple.

Importantly, FFO was not intended to be used as a measure of the cash generated by a reporting issuer nor of its dividend paying capacity. While dividends can be analyzed in comparison to FFO, as they are analyzed in comparison to earnings in other industries, it was and is not REALPAC’s intent to imply that FFO is a measure of the sustainable level of dividends/distributions payable by a reporting issuer. Given that FFO is not intended to be a measure of cash generated or of dividend paying capacity, REALPAC realizes that most analysts, in an attempt to evaluate dividend/distribution policy, may make a variety of adjustments to FFO with the desire to adjust it so that it would be a better measure of dividend/distribution capacity. These calculations generally are referred to by their authors as Funds Available for Distribution, Cash Available for Distribution or Adjusted FFO (“AFFO”).

FFO was created to be able to compare the valuations of companies. You may have lost interest half way through that quoted passage and may have missed this part, so I’ll repeat it.

Importantly, FFO was not intended to be used as a measure of the cash generated by a reporting issuer nor of its dividend paying capacity.

It’s funny that that is explicitly stated in the white paper that defines FFO, yet almost every REIT states its payout ratio in relation to FFO (and sometimes AFFO as well). Most investors will default to the FFO payout ratio as well when considering the safety of a distribution. And usually, I’ll admit, that is shortcut is fine. But scroll back up to the top of this post and look at Artis REIT’s Q3 statement again.

The FFO payout ratio for the quarter was 55%. The AFFO payout ratio was 100%. There is a very large difference there, and given the significance of the 100% payout ratio number (I know it’s just one quarter, bear with me), it’s important to know what has caused that big difference.

AFFO

Again, from REALPAC:

In consultation amongst preparers and users of reporting issuers’ financial statements, it was determined there was diversity in how AFFO should be utilized – some viewing it as an earnings metric, some viewing it as a cash flow measure, and others considering it a hybrid between the two. In order to develop greater consistency within the industry, it was determined that AFFO should be defined as a recurring economic earnings measure. For those using AFFO as more of a cash flow metric, REALPAC concurrently developed a new metric, Adjusted Cash Flow from Operations (ACFO). ACFO is intended to be used as a sustainable, economic cash flow metric.

Even AFFO isn’t meant to be a measure of cash flow, but as a “recurring economic earnings measure”, it is a decent proxy for our purposes.

REALPAC lists five adjustments to get from FFO to AFFO:

Capital expenditures (CAPEX)

Leasing costs

Tenant improvements

Straight line rent

Non-controlling interests in respect of the above

Capex in this scenario is maintenance/sustaining capex - the capex required to maintain buildings in their current state. It doesn’t include capital expenditures that improve the buildings. This is why AFFO is so often equated with free cash flow, which also is supposed to only deduct maintenance capex.

Here’s a wrinkle to this simple adjustment though - REITs are able to use their actual maintenance capital expenditures or use a reserve amount (ie. picking a number that it thinks represents a normalized average amount instead of having the number swing quarter to quarter). For the most part, I haven’t seen management teams misuse this, but I have noticed oddities. For instance, when I was looking at Morguard REIT, I noticed that it changed its reserve amount, cutting it in half. This is from the aforementioned unpublished post:

Morguard REIT uses “normalized productive capacity maintenance expenditures (PCME)” as its maintenance capex in the AFFO calculation.

Why I bring this up is because this year the REIT reduced its normalized PCME by half, from $25 million to $12.5 million.

This isn’t necessarily an egregious accounting game. Think about it: for almost half the year nobody was going into their offices. Many malls have had stores not open since March. Foot traffic through common areas is way down. Traffic in parking lots is way down. Maintenance capex is lower – buildings simply suffered less wear and tear this year. But is $12.5 million the right number? Was $25 million the right number before?

The REIT reports both normalized PCME and actual PCME, and actual has been lower in 2020 and was lower in 2019. That could mean that normalized is a safe estimate and AFFO is underreported. It could mean that Morguard REIT is underspending on its properties. With $2.6 billion (at its valuation) of mostly older real estate, it certainly seems to me like maintenance capex, the capex required to keep the buildings in the exact same condition as the year before, is probably more than $25 million.

This may or may not be material, but I do think it’s worth understanding. Someone who didn’t look may wonder why FFO/unit is down 31% YTD while AFFO is only down 24.4%. Well it’s because normalized PCME is down by 50%.

Without looking into how Morguard REIT calculates AFFO, you wouldn’t know that it was using a reserve amount of maintenance capex (PCME in this case), nor would you know that its actual expenditure had been lower than that for two years.

Capex is the adjustment most think of, and if you know REITs is probably the one you think of as the adjustment from FFO to AFFO the same way fair value changes are the adjustment from earnings to FFO. But those other adjustments are important too.

Non controlling interest is self explanatory.

Straight line rent adjustments are usually pretty small, and for the most part aren’t that interesting.

It’s leasing costs and tenant improvements I want to focus on.

Here is Artis REIT’s Q3 AFFO reconciliation:

Of the ~$40 million difference year to date, $23 million was its leasing cost reserve. Here is what management says about it:

Actual leasing costs include tenant improvements, tenant allowances and commissions which are variable in nature. Leasing costs will fluctuate depending on the square footage of leases rolling over, in-place rates at expiry, tenant retention and local market conditions in a given year. Management calculates the leasing cost reserve to reflect the amortization of leasing costs over the related lease term.

So Artis rolls up up tenant improvements (TIs) and leasing costs into one line, fine. No argument that they vary quarterly, or that a reserve can be an adequate way to account for this in AFFO.

If you look up in that picture, you see that TIs “amortized to revenue” and “incremental leasing costs” were $20.2 million, pretty close to the reserve amount. But that isn’t the number we want. We have to scroll further to find this:

Total leasing costs were almost $35 million. If you exclude the costs for properties under redevelopment, which would be akin to “growth capex”, leasing costs are still $33.5 million, exceeding the reserve by $13 million YTD. You can also see the leasing costs were well over the reserve for last year through Q3 too.

Anyway, these are minor quibbles but you can think for yourself about their ramifications relating to Artis. I’ll just show you one more piece of information that adds another wrinkle to this and I think is important to the Artis leasing costs/AFFO discussion:

Differential Reporting

What I want to finish with is just a brief glimpse at a handful of REITs showing you different reporting of AFFO. I mentioned Artis REIT and Morguard REIT, which both use reserve amounts for capex and/or leasing costs.

SmartCentres

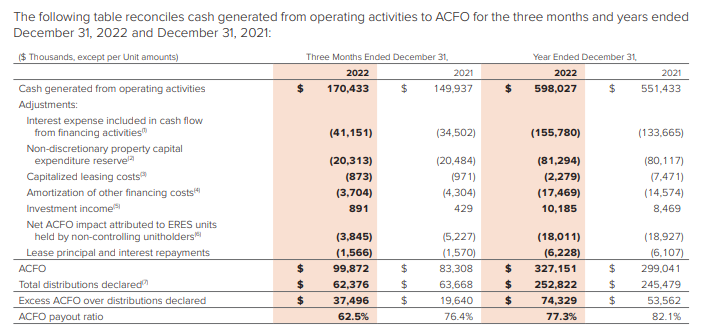

Here is SmartCentres’ reconciliation of cash flow from operating activities to adjusted cash flow from operations:

SmartCentres does not report AFFO, instead reporting ACFO, which you’ll recall:

REALPAC concurrently developed a new metric, Adjusted Cash Flow from Operations (ACFO). ACFO is intended to be used as a sustainable, economic cash flow metric.

SmartCentres reports FFO, to allow valuation comparisons to other REITs, but reports ACFO which it contends offers a better view of the sustainability of the distribution. That was REALPAC’s intention as well. It’s similar to AFFO, and when pressed I’ve used the two terms interchangeably, but it’s worth noting the difference. The numbers you need to calculate AFFO on your own are in the financial statements, if you so choose, but the number isn’t calculated for you.

CAPREIT

CAPREIT meanwhile, prominently features normalized FFO (NFFO) instead of AFFO…

which are not equivalent at all. If you look though, you will find ACFO calculated as well:

CAPREIT just doesn’t highlight that metric like SmartCentres does. ACFO isn’t mentioned at all in earnings press releases and is buried in the financial statements.

Plaza REIT

Plaza reports AFFO, and look how clean this reconciliation is.

Notably it uses actual maintenance capex and leasing costs, not reserves.

Riocan

Riocan has a messier reconciliation, and uses normalized/reserve numbers for capex.

Dream Office

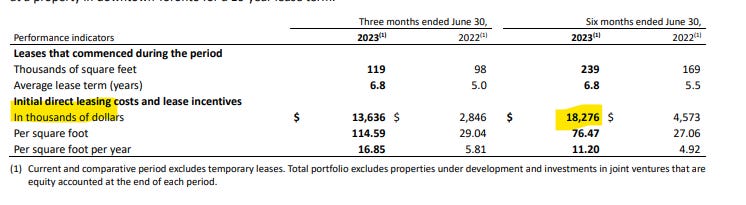

Dream Office does not report anything over and above FFO. However, you can arrive at AFFO (or a reasonable approximation) by doing some digging.

Above I showed you Dream Office reported $36.4 million in FFO in H1 of 2023.

Here we can see it spent $18.3 million on lease costs and incentives (incentives being equivalent to TIs).

Here we see Dream Office’s “building improvements”.

The financials go on to state that “recoverable” is essentially what is spent to make sure new rents will match old rents (ie they don’t add revenue, ie they are maintenance expenditures). So that’s another $8.1 million there, and given the office leasing market currently, it’s quite likely that some of those value-add improvements end up simply maintaining a property’s attractiveness to tenants (as tenants start requiring more from their landlords for little to no extra rent).

Elsewhere you can find straight line rent adjustment would be ~$500,000.

Just doing these adjustments would get us to an “AFFO” number of around $9.5 million for the first half of 2023.

Alternatively, you could look at Dream Office’s cash flow statement:

And if you deduct each of those red lines from operating cash flow, while adding the green line, you get -$420,000. This number would be similar to, but not exactly, ACFO. The only number there to quibble with is the building improvements; as we know management stated just $8.1 million of that was maintenance capex. Still though, whether ACFO is $0 or $4 million, the point remains the same. As an indicator of Dream Office REIT’s ability to pay distributions, it suggests Dream Office could hardly afford to pay any distribution at all in H1.*

*I know this is simply one six month period, and the prior year’s comparable period had much lower lease costs and would have a higher ACFO proxy. I’m certainly not saying Dream Office REIT could never afford its distribution, nor am I saying the distribution should be cut because of a temporary shortfall. You’d have to look at a longer time frame to state that, or make a prediction about the future. That’s beyond the scope of what I want to do.

Dream Industrial REIT

Just so it doesn’t seem like I am picking on Dream, Dream Industrial similarly doesn’t report AFFO, but if you calculate it yourself, the REIT’s AFFO is in the neighourhood of $110 million, while ACFO greatly exceeds the distribution.

Office REITs

For comparison, just because I find the contrast interesting, I’d like to show you the AFFO reconciliations of Allied Properties REIT:

and True North Commercial REIT:

Isn’t it kind of interesting that Dream Office REIT spent $18 million on leasing incentives (over $76/sq.ft leased!) and $8 million on maintenance building improvements in six months while Allied spent under $5 million through nine months and True North reserved just $2.5 million (just $0.50 per sq.ft of owned space!)?

One could make a few different conclusions from that, and I’ll leave that to you to make your own.

Conclusion

I could include a whole bunch more examples of AFFO reconciliations, honestly it was more fun than I expected, but I believe I have made my point.

FFO is one thing, and you can be reasonably confident those two numbers represent similar things at two different REITs. But REALPAC never meant for FFO to represent a metric to compare against distributions, so FFO payout ratios should be viewed very skeptically.

AFFO meanwhile can mean quite different things to different REITs. While using the number the REIT presents to you probably isn’t horribly off the mark - I have yet to see a reserve number that seems to be intentionally hiding something nor one that differed that much from actual costs - I think looking at those reconciliations is a worthwhile endeavour.

And if the REIT you’re looking at doesn’t report AFFO (or ACFO), you almost always are able to calculate the number yourself.

Thanks for reading.

Hey Tyler, thanks for the article. Big fan of your work.

Quick question though. Noticed that FFO/AFFO calculations don't seem to take into account required principal repayments on mortgage debt. Am I wrong in this observation? Wondering how you think about these principal repayments, as they can be quite sizeable for REITs.

Great article, I loved reading it and I learned a lot. thanks for sharing.