See here for the previous Meandering Post, written in summer 2020

Dream Unlimited has gotten some attention from investors. This is most apparent, to me anyway, from the amount it is discussed on Twitter without me contributing. For a good while, if you searched $DRM.TO on Twitter, the results were almost entirely my tweets. Now though, since the start of the year 15 people have tweeted about it using either $DRM.TO or $DRM. This terrible survey method doesn’t include anyone that has discussed it without using those symbols, nor does it include any of the many accounts I choose not to see on Twitter.

Among the pick up in Twitter activity, there have been several people who have written longer form pieces about the company. Which means… nobody needs me writing about Dream.

When most people, myself included, write about Dream, they understandably choose to focus on the valuation of the company. Specifically, most choose to look at the value of the assets, then compare their net asset value or sum of the parts to the stock price.

It makes sense. As I said, I have written about the sum of the parts and have often thought about it. NAV is how the company seems to think about its value and it’s how analysts tend to think of it. If you want to read a sum of the parts of Dream, you have come to the wrong place. You can get that anywhere these days, including from the company. I have doubts whether my writing adds any value at all (hence why it has been so easy for me to stop writing (the doubts being reinforced by seemingly nobody noticing or caring that I have stopped writing or using Twitter to publish thoughts)), but it certainly doesn’t add value if I regurgitate what the company publishes, or what you can find easily elsewhere, often written better than I would have.

But it’s been a long time since I wrote about Dream. And nobody in the real world seems to care what I have to say about it. In lurking on discussions of Dream, I see some questions or concerns brought up regularly. And there are a few thoughts I’ve had kicking around my brain. In the absence of an alternative outlet for them, I figured I’d write them down here.

Big Run Up

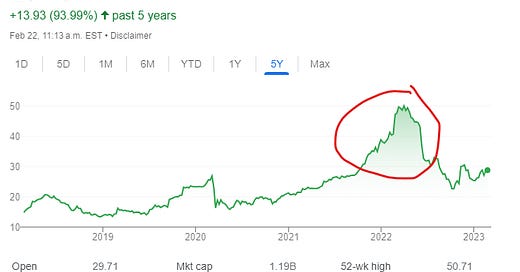

Late 2021 and early 2022 represent a pretty significant outlier in Dream’s stock price performance (as opposed to actual performance of its business). Smarter investors than I likely took that opportunity to sell their shares, take profits, lighten up, etc. You can call this hindsight (and it is), but I don’t think it takes a genius to think it makes sense to own less of something when it is at a 20% discount to its fair value than when it is at a 50% discount (insert whatever numbers you want there).

Looking at this chart, it’s hard not to kick yourself a little bit.

I am acting like I’m mourning my mistake here, but I’m mostly joking. The light green line on the chart implies two things:

Michael Cooper and Dream have been creating value at a very good rate.

Analysts are not great at estimating NAV.

Even as the share price approached NAV, I was okay holding onto my shares as I believed they’d offer a satisfactory return through NAV growth and dividends, even if I didn’t have the return from the NAV discount shrinking. I haven’t changed my thoughts on that (Dream growing value enough to offer shareholders a good return even without multiple rerating), but I have possibly changed my investment philosophy that I may act differently should Dream trade so close to its NAV again. We’ll see, but that’s a topic for another day (or not actually, since I probably won’t discuss it).

What I want to discuss more than what happened is my theory on why. It clearly was an anomalous situation, and I think it was a perfect storm of three factors.

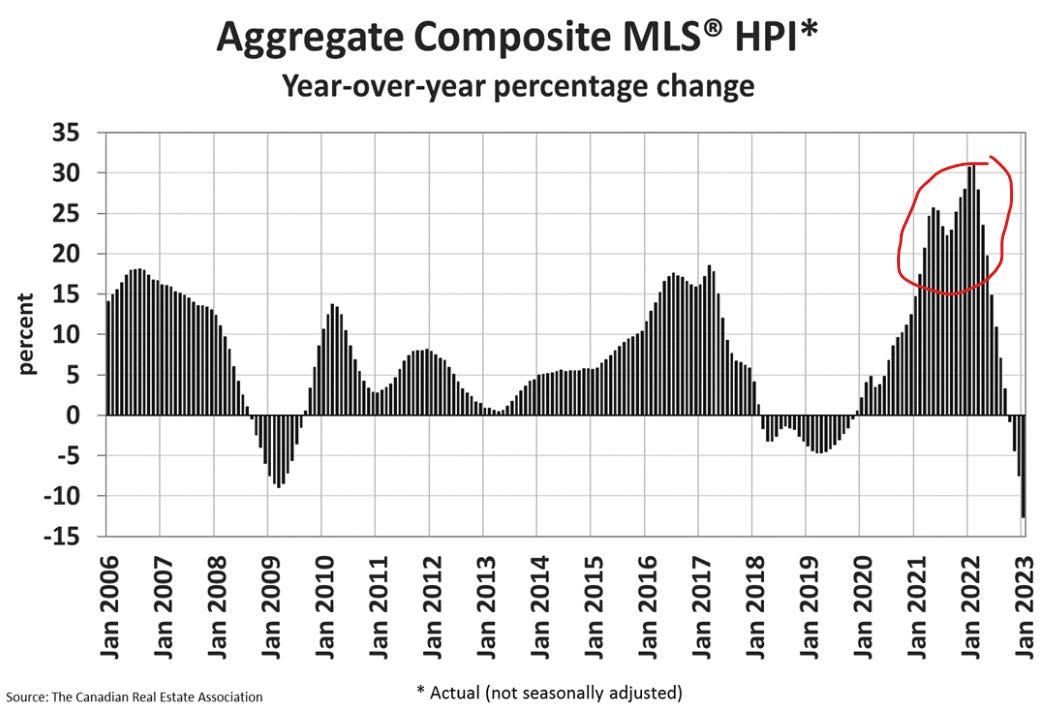

Number one is the general real estate hysteria that was going on at that time. Two charts showcase the hysteria at the time well, along with the hangover weighing on Dream’s stock price now.

I’d love it if those X-axes lined up but as you can see by my poorly drawn circles, Dream’s stock was flying while home prices were going crazy and home sales were elevated. This obviously affected the sentiment around Dream - people are going to be more willing to buy a real estate owner and developer when home prices and sales are higher - but it also likely affected people’s beliefs about how much money Dream would be making. I for one had visions in my head about Dream selling 1200 Western Canada lots a year and selling condos in the GTA for $2000/sq.ft. Oh well…

This wind has shifted from a tailwind to a headwind, and now sentiment around Dream’s stock is fighting the opinion of so many that home prices are going lower, and the fact that so many people are delaying buying/selling homes. This alone likely would have made an upside down V pattern on the stock chart.

But as this was happening, all through 2021 Dream was also posting a bunch of good news about its asset management business. Fee earning AUM increased from $5 billion to $9 billion in 2021. Dream launched a private impact fund, a private US multifamily fund, a US industrial fund, a property technology joint venture, and made plans to launch Dream Residential REIT. Asset management had been a big part of many an investor’s thesis, had been talked up by management, and therefore it was a key performance indicator for many. It going so well so quickly was confirmation of the company’s performance and added some fuel to the stock price fire. The good news hasn’t stopped, in fact it has only continued, so I won’t point to this as a reason for the later stock drop.

Then 2022 started off with the news that Dream had won the first phase of Lebreton Flats in Ottawa, and then February 15th, about a month before the top, Dream was selected to take over the former Sidewalk Labs project Quayside. These were huge wins in general, a developer winning big newsworthy projects is always going to be good news (assuming a good price is paid, a big assumption I know), but these projects in particular were also seen as confirmation that Dream was finding success with its impact investing approach to development. Dream won these projects in large part due to the affordable homes and inclusive communities it proposed building. I doubt many people increased their estimates of Dream’s future project wins, but I bet many started thinking Dream would win more projects due to this. I had the thought, even if it didn’t affect what I thought Dream’s NAV was.

Finally, and what I’d argue was the second biggest reason for the stock’s odd performance (huge run up followed by pretty quick crash) after the real estate market, is Dream had a big buyback program all through 2021 and the first quarter of 2022, then quit buying back shares all together in Q2 2022.

In 2021, Dream spent over $60 million buying back 2.4 million shares, which was about 10% of the public float. In Q1 2022, Dream spent another $15 million buying back 400,000ish shares. When the all time high was reached on March 14th, and the stock started a precipitous, relentless fall in late April, it’s impossible to deny that Dream’s buybacks did not play a huge roll in the climb of the share price.

I’m not saying this critically. I think many would lament the company buying back shares over $40 when the stock is now under $25, but I won’t. If I think the stock is worth $60 or more (which I did), I’m not going to be upset about buybacks at $45.

The fact of the matter is, after buying back almost 8 million shares in 2020 (at prices not far from today’s), there just were not many willing sellers left in 2021, so buybacks could not help but move the price (despite rules aimed at preventing that). Then, when Dream stopped buying back shares, the biggest source of buying pressure was gone, and the stock couldn’t help but go down. I’ll admit that I was surprised by how much the price went down, but combine this with the real estate market and it’s not too shocking.

I think this look back is a bit informative, because the same conditions could very well arise again.

I will not waste your time or mine by trying to predict the Canadian housing market. Many other smart people will do that for you (though I’m dubious whether reading those predictions is any less of a waste of time), but I don’t think it’s crazy to think that home prices might be higher in X years than they are now. I’m not predicting that, and if I were forced to place a bet on it in the next five years I’d probably bet against it, but it’s not out of the realm of possibilities. If that did happen, again through a combination of sentiment shifting and more profits being made, Dream very well could rerate again. This is just something to keep an eye on, not something to bank on, nor do I think it can guide investment decisions.

More instructive though is the look at the effect that buybacks will have.

Michael Cooper has stated that paying dividends will be more of a priority than it was before, which has to come at the expense of something, and that something is likely to be buybacks. The days of SIBs seem to be over (outside of any windfalls earned or crazy mispricing possibly), but Dream seems very able to buy back 1-3% of share’s outstanding while also achieving its apparent goal of becoming a dividend growth stock. We saw in 2021 what 5% of shares being bought back does to the stock price - causing at least some portion of that year’s 82% gain. What effect would buying and cancelling 1% each year have? I do not know, but with Cooper’s 50% ownership and the rest of the stock held pretty tightly, I believe it would have some positive effect.

Asset Management

In my previous Meandering Post, I threw out a very half assed guess:

I’m basing this on essentially nothing, but let’s imagine the future a bit. Cooper hinted at breakeven in three years, who knows what that would mean for AUM, but let’s say at that point Dream is at $1.3 billion AUM (roughly what Westaim‘s Arena Investors is at, and Arena is around breakeven), and Dream gains $500 million to $1 billion a year in AUM thereafter (at say 1% fees before performance fees). In 6 years DEP could be earning like $20 million, and still growing rapidly. Add that to maybe $10-$15 million from managing the subsidiaries. What would such a business be worth? I would say such a business is worth more than 15x earnings. At 15x Dream’s asset management platform would be worth over $11 a share.

While it’s not clear, I was just talking about $1.3 billion in private funds, which doesn’t include the publicly traded REITs. And the number gets a little more screwed up because Dream has done JVs, and seeded funds with Dream Industrial REIT’s assets, etc. Dream claims to have $8 billion in private vehicles, including the Dream Industrial REIT/GIC JV which purchased Summit. Excluding that, and only counting outside funds, my $1.3 billion estimate isn’t so far off.

When you consider that JV, and the management of the REITs, you start getting an idea about the value of the asset management business.

In 2022, Dream claims $17.4 million in asset management EBITDA. That is with half a year of the GTA land JV, no contribution from the Summit JV, and just over half a year of Dream Residential REIT.

All of the different funds and JVs have different fee structures, and they’re not often disclosed, so I am not going to bother with an estimate of what 2023’s EBITDA might be. But in that paragraph above I threw out upwards of $35 million in earnings in 2026. Assuming we get some modest capital raising in the intervening years (and that Dream charges GIC a decent fee on the Summit JV), I don’t see how $35 million in 2026 is anything but conservative.

I’ve been beating the asset management drum for a while now, and others have caught on (TD values the asset management business at $677 in its newest NAV estimate), but the market as a whole doesn’t seem to be valuing it in line with how it has performed (or else its valuing a lot of other good assets at firesale prices).

Dream Industrial REIT Incentive Fee

Another drum that I have been beating is valuing the Dream Industrial REIT incentive fee that Dream Unlimited could earn by selling the REIT.

As background, when Dream sold Dream Global REIT to Blackstone in 2019, it earned $400 millionish dollars as a result of its incentive fee structure with the REIT. The same structure (more or less) is in place with Dream Industrial. Hence, it made sense to me, not to count on the fee coming, but value it to see what it would be if it did come. Again, from the first Meandering Post:

The last thing I’ll mention about the future, that I don’t think enough people are considering, is the incentive fees Dream is set to earn from Dream Industrial at some point in the next five to ten years. I figured in that Dream Industrial post that if Dream sold Industrial in just a couple years, Dream was set to receive something like $220 million in incentive fees. Every year that goes by without a sale, those incentive fees are going to grow. The incentive fees are 15% of AFFO above a hurdle. The hurdle rate goes up by half of CPI annually. I don’t think it’s taking a leap to say even just same property growth would lead to AFFO increasing by more than inflation. Then you add AFFO from future acquisitions, and the AFFO that comes as a result of the eventual sale, and, as much as I’d love for DRM to receive ~$5/share in cash, the best thing to do is to just keep building Dream Industrial. Just know that there is a $220 million asset growing at essentially the same rate as Dream Industrial is, that one day will be realized. I know the market isn’t paying attention to this.

Recently, Dream Industrial has stolen some of my thunder and started publishing the fee itself.

Check off another reason for why I don’t need to write anymore.

At one time, I sort of expected that news of Dream Industrial’s sale could come at any time. Industrial REITs were hot, hot, hot, Blackstone had essentially unlimited capital, interest rates were zero, and why wouldn’t Dream want to take in a $6/share windfall that is so easy to collect.

Most of those reasons still hold, and I think Cooper could sell Dream Industrial REIT anytime he wants with at most, two phone calls, but I don’t think the sale is coming any time soon.

The first reason is that Dream Industrial REIT is so close to paying incentive fees each year for passing the FFO/unit hurdle rate. The hurdle is $1.00, and in the fourth quarter of 2022, FFO was $0.23, 10.4% higher than Q4 2021. Add on to that the Summit JV, which will earn the REIT FFO both in the form of its 10% ownership stake and the fees it will earn for property management, as well as the FFO growth that will come from acquisitions, developments finishing, and organic growth, I believe that Q2 2023 will probably show run-rate FFO over the hurdle rate (likely to be $1.03ish for 2023). That means that the REIT likely ends up paying Dream incentive fees in 2024 even without a sale. They won’t be much - 15% of FFO over the hurdle means that for each penny over the hurdle Dream’s incentive fee is roughly $400,000 (which conveniently happens to be one penny per Dream Unlimited share) - but they’re something, they’re pure profit, and they're bound to grow.

The fee upon a sale is also bound to grow quickly though. Assuming that the REIT could be sold to a big buyer at NAV, Dream earns 15% of NAV growth going forward. A $1 increase in NAV would mean the incentive has grown by $40 million or so (~$1/share). With Dream Industrial spelling out the incentive so plainly, the growth has become very obvious. At Q3, the fee was $250.2 million; the fee grew by $21.5 million in one quarter. With numbers like that, why would you sell out?

Finally, the growth of Dream’s industrial funds is essentially unlimited now. GIC has something like $700 billion under management, 10% of which is invested in real estate. If Dream Industrial REIT identifies an opportunity, and can convince GIC to invest alongside it (presumably Dream seems able to make that phone call), what out there is to big? Summit is the second large portfolio transaction Dream has made (the first being Dream Industrial’s European expansion). It’s quite possible that with unlimited capital, Dream would want to do more large industrial acquisitions. While that possibility doesn’t go away if Dream Industrial REIT is sold off, it at least makes it more difficult (the REIT’s fundraising ability in the public markets still being valuable).

What this leaves us is a $272 million growing asset which is unlikely to be realized anytime soon. Pretty soon you can value the incentive fee based on the annual payments to Dream (do a DCF of $400,000 year one, $1.6 million year two, etc) and you can probably calculate a pretty substantial figure. But each quarter Dream Industrial is going to tell you what the incentive fee in the event of a sale has grown to, and you’ll have to decide for yourself what its value to you is. It isn’t easy. I don’t know what the value is, but I know it isn’t zero.

Dividend Growth

In February 2019 Dream announced it would start paying an annual dividend of (reverse split adjusted) $0.20. Each year it has increased:

2020 - $0.24

2021 - 0.31

2022 - $0.40 plus a $0.50 special dividend

In 2023 the dividend has increased to $0.50. Michael Cooper has talked about it a bit, and he has backed up the talk. Dream is going to be a dividend growth stock.

To start with, Dream can absolutely pay this dividend, and can keep growing it. Once again, Dream has started doing some investor relations, and the company included this slide in its newest investor presentation:

I love this company but the choice of colours on this chart is is borderline unforgiveable

Dream earned roughly $100 million from its recurring income sources (asset management, owned properties, and distributions from the public income trusts). That $100 million exceeded fixed costs by almost $15 million.

Assuming that the company will not raise the dividend to exceed recurring income, Dream could have paid a dividend of almost $0.70.

Interest costs are likely to rise, as will overhead, but we also know that recurring income will grow. Arapahoe Basin will likely grow its earnings as long as weather isn’t drastically worse next winter. Asset management earnings will be higher. Income properties will earn more money - Dream has about 200,000 square feet of commercial properties it will hold (at its share) finishing in 2023, as well as about 300 apartments (again at its share, not including those held by funds) and its new Postmark Hotel in Newmarket. Add those to the $160 million of property acquisitions Dream made in 2022 (this includes both Dream and Dream Impact’s spend, but I don’t want to search out or calculate the standalone figure) and all the buildings that finished in 2022, therefore not having contributed a full year to earnings.

It’s probably not the right way to think about it, but I’m a simple man, and looking at recurring income funding the dividend and development earnings funding buybacks and reinvestment seems like an illustrative heuristic to me. How high will recurring income grow in the next few years? No idea, but I know that in 2025 the recurring income will be well over $100 million.

Dream could grow its dividend 10% a year for four years before it would exceed the $0.70 it could have afforded this year. Given the stated goal of paying dividends, the growth we’ll see in recurring income, and the low payout ratio now, I think we’ll see very impressive dividend growth for a long time.

2024 will mark its 5th consecutive year of increasing its dividend, making it a dividend aritstocrat, eligible for inclusion in that index and to be bought by the $1 billion CDZ ETF (Dream may not be eligible for liquidity reasons or some such thing but I didn’t look up the eligibility rules closely). The dividend growth investors will start taking notice of Dream. Folks who want their real estate exposure to come with some cash flow will start taking notice of Dream.

While I would not choose to the same capital allocation path - I’ll be the first to acknowledge that this is partly rationalization on my part because I realize the days of huge buybacks are over - I do understand it, and can see its appeal. I won’t lie, I really like seeing my dividend income rise despite it being absolutely not my goal and it not being a consideration in my investing decisions. I may sigh a little when I see those dividend guys talk about getting a raise because Enbridge increased its dividend by 2.2%, but also, my lizard brain gets it.

Western Canada Land

I’d like to skip the obvious “the land is worth more than its balance sheet value” talking point. You can find that anywhere. Quickly though, TD claims that the land inventory, valued at $470 million on the balance sheet, is worth roughly $1 billion. That seems fine to me.

What I find interesting about Western Canada, that isn’t getting talked about much, is Dream building and holding onto income properties on its own land out there. I’d have to go back and look, but I believe I invested in Dream in late 2018 or early 2019. At the end of 2018, Dream owned 280,000 sq.ft of commercial properties out west (its share), valued at $68.5 million. While some of this space was completed and had tenants in it, the properties were still being built out.

Today, Dream owns roughly the same amount of commercial space with higher occupancy (72% then vs over 90% now), and the developments will be finished by the end of 2023.

More than that though, Dream currently has finished 169 townhouse/apartments in Saskatoon that are 100% leased, and this year will be finishing another 227 units. In last year’s Q4 call Cooper talked a bit about this shift:

The part that is interesting is on the first apartment that we built in Brighton, if you use land at fair value, we made CAD5 million by building that building on 1.5 acres and we're doing it again. So we're going to try to get a lot more value out of less real estate going forward. So I think you'll see that with the townhouse and everything else, it will be good.

I was excited about it then, in general I’m a big fan of Dream owning more multi-res and like the Western Canada residential space. At the time, the townhouses were talked about as an experiment, but even with valuing the land it built its townhouses on at $1 million/acre, Dream built out the townhouses at a 6% cap rate. To me the experiment seemed a success - make very good money on your own land while building residential units to rent out at attractive yields. Since that call Dream has listed that it is in the planning stage for another 95 townhomes, and the finished units have remained 100% occupied, so it seems Dream agrees the experiment was a success.

I think this creates an obvious fifth lever to create value on its land. As it stands, with an acre of Western Canada land, for all intents and purposes Dream can:

Develop it then sell lots to homebuilders

Develop it and build homes itself to sell

Sell large chunks/acres to others

Build a commercial building to hold and rent out

Build apartments/townhouses to hold and rent out

That new fifth option should prove to be very valuable, specifically in an environment where new home prices have gone down and sales have slowed.

If I can toot my own horn a bit, there’s a lot in that first Meandering Post that looks pretty good in hindsight (the total return of the stock makes me look pretty bad though, lest you think my head is getting too big). I want to talk a bit about this though:

Most of those projects are targeting occupancy/stabilization in the next two years, so by 2023 Dream is going to resemble more of a straightforward real estate company, as opposed to the real estate/developer/asset manager chimera it looks like now. At that point maybe Dream starts reporting FFO like other asset managers (Tricon, Brookfield, Melcor) have done since apparently real estate investors can’t get their head around other metrics. Maybe Dream boosts the dividend even more since it requires less cash to develop land and the cash flow it has is more dependable. Maybe Dream spins off another REIT. Who knows, but the company will look very different, almost certainly different in a way that it is easier for investors to see the value they are missing now.

Dream doesn’t look more like a straightforward real estate company (and the newly announced Avrio lending arm just makes it more complicated), but other than that:

Dream has had a lot of projects finish, and it has acquired lots of income properties. At Q2 2020, Dream Unlimited had about $430 million of income and recreational properties on a standalone basis. Today, that number is now $1.2 billion.

Dream has boosted the dividend and has commited to keep doing so, as discussed above.

Dream did issue another REIT, though it wasn’t a spinoff. Dream Residential was IPO’d a year ago. When I wrote the above, Dream didn’t own a single US apartment, now it manages over 6000 through a public REIT and a private fund, along with owning a portion of each of those.

The company does look very different now

Where I was wrong is that by 2023 Dream would be easier for investors to understand. Big swing and a miss.

I’ll admit we’re getting there. Disclosing the recurring income earnings and discussing them, as done in the presentation and conference call, that’s good. But if you will indulge me, please open Dream’s 2022 annual report and tell me how much cash was brought in by the Western Canada development business. I’ll wait…

If you went and looked, I’d be curious what you came up with. I have probably spent as much time in the last 3 years studying Dream Unlimited as anybody not named Cooper. I personally have no idea. The reason is clear from this discussion of the results of the development business:

In the year ended December 31, 2022, our development business generated $175.8 million in revenue and net margin of $24.0 million, down from $209.2 million and $27.1 million, respectively, from the comparative period. The decrease was driven by lower condominium occupancies, which is in line with management's expectations and was partially offset by higher acre sales in Western Canada.

Included in the development segment results for the three and twelve months ended December 31, 2022 is a $54.8 million fair value loss on Dream Impact Trust's investment in the Virgin Hotels Las Vegas.

The economics of developing land out west is obscured by Dream Impact and the Ontario developments.

One of the best pushbacks I’ve ever got about Dream is someone asking just how profitable the Western Canada developments are. His point was, we (people who discuss this company on the internet) are always saying that the land out west is on the balance sheet at cost, it’s worth a whole lot more than that, hence book value is understated. We know that to be true, but despite that, it never really shows up in margins. Or at best, it does but it’s covered up.

To be frank, my retorts to the criticism were less than satisfactory. To sum up:

How could it not be profitable? We know Dream fetches $600,000 per acre in acre sales, and we know its land is held at much less than that. We also know Dream sells lots for well over $100,000 ($134,000 in 2021, $140,000 in 2022).

We can go back to Dream’s early years when the development segment was better disclosed and get an idea of how the margins would look without the Ontario developments.

Genesis and Melcor do make it possible to see how much they make developing land in Alberta. There’s no reason to think Dream operates less profitably (and the cost base gives reason to suggest it could be more profitable).

Those aren’t quite leaps of faith, but you can see how your run of the mill investor isn’t going to do it. I do not blame anyone that finds Dream complicated.

More than buybacks, more than dividend growth, more than shifting to more recurring income, more than almost anything (I’d say almost everything but fee earnings growth and a big shift in office and/or home prices outlook), I believe simplifying the financial disclosures would do a lot to improve Dream’s valuation.

Look at Brookfield. It’s as complicated a company as there is out there. Brookfield reports its IFRS earnings. It also reports the FFO of all its segments, then a total FFO number. Then a distributable earnings number both before and after realizing carried interest and gains from asset dispositions. A discussion of the validity of Brookfield’s numbers is beyond the scope of this post about Dream, but the point is that Brookfield goes above and beyond to help investors understand its business, a business not so different from Dream’s.

Here is what Dream reported in its 2022 earnings press release:

Those are the IFRS required numbers. Complicated, consolidated. I doubt you could look at those numbers and be confident you knew how the business truly fared.

Here’s the supplemental disclosures Dream gives in its press release to help understand what’s going on:

The shareholder’s equity per share is a nice touch, but other than that, not the most helpful.

Now this is a good start. It’s only the recurring income segment, and it’s still a little clunky, but this disclosure increases my understanding of the business. I have a better idea of what the asset management business earns because of these tables. It’s the clearest Arapahoe Basin has been disclosed. As stabilized properties increase in importance to the company (the year ended 2021 table didn’t fit in the screenshot but the stabilized properties adjusted EBITDA number was just $20 million in 2021), this table will help you see how they perform.

But that’s it. These same adjusted EBITDA tables for the development segment, splitting up Western Canada and Ontario, would be incredibly valuable.

The annual report has a whole bunch more info in it, but it takes a lot of work to get a better idea of the results than what the press release says, which isn’t much.

In comparison, here’s Brookfield Corporation’s 2022 earnings press release. I’m going to skip a bit since the press release has so much more in it:

This is right at the top of the press release. The IFRS required number, then FFO and distributable earnings.

This is a little ways down, but tells you how each of the above numbers is reconciled.

A breakdown then by each segment, giving you an idea of the performace of each one (which would be missed just looking at the total FFO number).

I’d like to see, if not that exact reporting, something similar. A distributable earnings or similar number in my mind is going to be one of the most important numbers for investors going forward. A company wide FFO number would allow Dream to be compared to its peers. As mentioned, in addition to every REIT and real estate company, Dream’s closest peers - Tricon, Melcor, and Brookfield - all report an FFO number to investors. I’m not saying an FFO multiple would be the right way to value Dream (or the others), and I’m not saying FFO would be the proper way to evaluate the business. I am saying that it would be another tool available to investors, and I do not see a reason not to report a number that everyone in your industry reports, including three very similar peers.

And finally, reporting segment FFO numbers would assuage the concerns of those like my friend I mentioned, and would give everyone greater clarity on what the economics of the various business units are. Imagine Dream reporting something along the lines of Brookfield’s segment FFO table, splitting up asset management, stabilized properties, Arapahoe Basin, REITs, Western Canada development, and Ontario development. I get that that would be a bit messy, the Ontario development segment in particular would be very volatile, but there’s no way you can convince me Dream wouldn’t be more understandable with these disclosures. And there’s no way that Dream’s stock doesn’t trade higher if the company is easier to understand.

NAV → Cash Flow

Dream has always been an asset story. Bulls would go through the assets, determine a fair value for them, then come up with a sum of the parts, which would usually (always?) exceed book value. Regular Joes would look at book value, and typically Dream would be trading at a discount to book so that was also a bull case.

The company is different today, and I think Dream can be looked at as a cash flow story now. With some reporting changes, it would be.

In 2022, just the recurring income cash flows exceeded interest and G&A by ~$31 million. That number has actually been pretty consistent, but with some cost discipline, which I don’t think Dream can help but show, this is bound to grow a lot.

Over the last few years, the development segment has earned net margins of:

$55 million in 2017

$27 million in 2018

($20 million) in 2019

$52 million in 2020

$27 million in 2021

$24 million in 2022

I’m missing some consolidation nuance there, but the development segment had average net margins of almost $30 million before any contributions from equity accounted investments, which make up a significant portion of the segment’s earning power. Indeed, the segment’s earnings from equity accounted investments have averaged another $12 million, and if you exclude 2017 and 2018, before it had much in the way of equity accounted investments it averaged ~$20 million (development equity accounted assets went from $40 million in 2018 to $188 million in 2020 and $317 in 2022, again with Impact consolidation screwing things up a bit but directionally correct).

The last six years have covered a wide variety of environments. Oil was priced poorly for most of that, affecting demand for new homes in Western Canada. COVID happened, which obviously had significant ramifications both negative and positive. And now we’re in a rising rate (or at least not zero rate) environment hurting home affordability and prices. Yet Dream had a lumpy but brought in a consistent $30 millionish from its developments.

Combine the lumpy $30 million a year from the development segment and the growing $30 million from the recurring income segment, and Dream is trading at something like 16x earnings. 16x conservatively estimated (ignoring a lot of the earnings) and quickly growing earnings seems like a good price.

Alternatively, let’s just look at Dream’s standalone net earnings excluding fair value gains. They’re lumpy, but:

$70 million in 2017

$66 million in 2018

$345 million in 2019

$93 million in 2020

$95 million in 2021

$116 million in 2022

For three years running, standalone earnings without fair value changes have been around $100 million. That would put Dream at under 10x earnings. Under 10x earnings for a company turning dormant assets (land) to cash and income producing assets. A company that has grown fee earning assets from $5 billion to $17 billion in the last two years. A company that is shifting to steadier earnings. A company that could, I hope, become easier for investors to understand. A company that could attract a new demographic of income investors.

A company that is facing a difficult environment, no doubt, but one with a leader who has grown this business 20% a year for almost 30 years, who started a business with $500,000 that now earns more than $100 million a year.

If Dream can find a better way to communicate the earnings and cash flow of its business, I think Dream can become a growing earnings story instead of a sum of the parts story, which many are understandably not interested in.

It’s not all rosy

This isn’t to say I’m under some illusion that Dream isn’t facing difficulties.

Office buildings are undoubtedly struggling. Dream Office has had FFO go from $1.70/unit in 2019 to $1.52/unit last year. Interest coverage has gone from 3x to 2.5x. Debt to EBITDA from 7.5x to 10.4x. Occupancy from 90.8% to 84.4%.

Dream (and Dream Impact) are trying to sell and start construction on a luxury condo (Forma) under terrible circumstances for it. Sales have been better than expected, but seem to have come to a standstill lately (seasonality plays a role but still).

Dream has a lot of projects under construction which have had inflation play on costs, and interest rates affect selling prices and/or valuations. It wouldn’t surprise me if a few (or more) of the projects under construction and/or finishing soon are pencilling out very differently than they were originally budgeted for.

You don’t need me to explain how how rising interest rates affect real estate values. If interest rates remain at these levels (or higher) for longer than expected, that will weigh heavily on the value of Dream’s assets and the sentiment of the market.

Conclusion

This was my conclusion to my first meandering post, but I really like it, so I’m going to reuse it with updated numbers. I striked through a few of the old numbers to show you how value has grown in the interim.

I know besides me there are about ten people who care about Dream Unlimited, and I doubt Michael Cooper or anyone at Horizon Kinetics is reading this, so I appreciate it if you slogged through this rambling.

After all this blabbering, what is Dream worth? I really can’t say. It could be $28 $33.50 (standalone book value), it could be $30 $35-$45 (20x 15-20x normalized EPS earnings before fair value gains), it could be $43 (TD target price), it could be $70 (TD’s NAV estimate), it could be a lot higher. If we work under the assumption Dream can earn double digit ROEs in the future and grow book value in the high teens, you can justify pretty high prices. I am specifically not making those assumptions nor do I want to convince you of them. More to the point, I think you have to make wilder assumptions to justify $17 $23 than you do to justify $30+.

Dream Unlimited is a fat, fat man. I don’t know if he weighs 300 lbs or 400 lbs or 500 lbs. I know he’s not 230 lbs though. And I know he’s going to keep overeating.

Thank you for sharing, always very thoughtful and insightful!

Wow, thats a pretty extensive article. Ill check that stock out, thanks.