I admit that I am probably late to the gold party. I feel like an idiot for it. For quite a while, I’ve seen smart people discussing the reasons why gold would increase in price. One of those people has even made me a bunch of money on a gold mining stock before, with his open discussion of Gran Colombia Gold, still one of my best investments - shout out

. I watched the price of gold go up every day for what feels like far too long now, and for a variety of reasons never bothered looking into either gold or miners.I want to blame at least a decent portion of my tardiness on Warren Buffett. Although he said it quite a while ago, whenever I think about gold I think about this quote:

Today the world’s gold stock is about 170,000 metric tons. If all of this gold were melded together, it would form a cube of about 68 feet per side. (Picture it fitting comfortably within a baseball infield.) At $1,750 per ounce – gold’s price as I write this – its value would be $9.6 trillion. Call this cube pile A.

Let’s now create a pile B costing an equal amount. For that, we could buy all U.S. cropland (400 million acres with output of about $200 billion annually), plus 16 Exxon Mobils (the world’s most profitable company, one earning more than $40 billion annually). After these purchases, we would have about $1 trillion left over for walking-around money (no sense feeling strapped after this buying binge). Can you imagine an investor with $9.6 trillion selecting pile A over pile B?

Beyond the staggering valuation given the existing stock of gold, current prices make today’s annual production of gold command about $160 billion. Buyers – whether jewelry and industrial users, frightened individuals, or speculators – must continually absorb this additional supply to merely maintain an equilibrium at present prices.

A century from now the 400 million acres of farmland will have produced staggering amounts of corn, wheat, cotton, and other crops – and will continue to produce that valuable bounty, whatever the currency may be. Exxon Mobil will probably have delivered trillions of dollars in dividends to its owners and will also hold assets worth many more trillions (and, remember, you get 16 Exxons). The 170,000 tons of gold will be unchanged in size and still incapable of producing anything. You can fondle the cube, but it will not respond.

I’m sure the cube would be bigger than an infield now, but the point stands. Buffett had me thinking gold wasn’t worth my time. However, I was never going to be investing in gold directly. Somehow when I was younger and made that investment in Gran Colombia, I knew I didn’t need to have a view on gold. I was investing in a company that sold a product. Sure the price of that product could be volatile, but it was a product that would probably continue to have demand. I hardly know enough about business to be writing on the internet (I'm always amazed so many people follow my thoughts), but I know far less about currencies or macroeconomics or anything that would help in making a gold price prediction.

Now though, the price of gold is $3,300 USD/oz. It’s up some absurd amount over the last year and a bit and if there is one thing I really like doing, it’s analyzing a company with some easy discounting applied. And it’s very easy to analyze a gold company based on different prices of gold.

When I realized I was standing on the docks watching the gold boat sail away, I thought there was a chance that there were gold companies out there that were priced reasonably - if they weren’t still tied to the dock, maybe they were at least within a stone’s throw of it.

There are a few gold stocks that I kind of keep an eye on, so the first thing I did was look at those. Boy did it suck seeing all these charts look like this:

Admittedly, you can find time periods on these charts that would correspond to relatively poor returns, but for the most part these companies are all much higher than when I was paying closer attention to their stock price.

While the charts sting, I don’t kick myself too bad as I never really took a close look at any of these. It’s not like I looked at the financials and turned them down. No, at best I may have looked at the investor presentations, not been blown away, and moved on.

The exception is Globex, which I thought was much more dependent on commodity prices (since its assets were small and relatively unlikely to be mined without some big bull market and it had only nominal cash flow), and Sailfish, which I actually did buy around $1.30, though I believe I sold it shortly afterwards and not a lot higher.

My analysis of Sailfish was very rudimentary, though it didn’t need to be particularly exact. Sailfish owned a few royalties/assets, and several of them had recent comparable transactions which made it very easy to come up with a sum of the parts value:

Sailfish had just sold half of its Tocantinzinho royalty, so I knew what a buyer was willing to pay there. And Osisko Royalties had just purchased a royalty at Spring Valley and Moonlight, making that a very easy piece to value. Once you came up with values for those, Swordfish (a planned spinoff of a silver mine) and the cash were kind of immaterial, so all you had to decide was whether Sailfish’s royalty at San Albino (and all the land surrounding it, which I’ll get to) was worth more than $27.8 million. That was an easy decision at the time. While San Albino wasn’t in production, or was close to it, production was right around the corner and it wasn’t hard to come up with cash flow estimates that justified the implied value and then some. If I were smarter - by which I mean smarter (to better understand pre-production gold mines) as well as more diligent (to know to always dig a little deeper) - I would have looked more closely at San Albino to have done the work on both Sailfish and Mako. At the time Mako was actually priced very similarly to today, so I can’t imagine I would have bought it then, but during those periods in late 2022 and 2023 when the stock was very beaten up, it would have been nice to be familiar with Mako. Alas, I’ll have to settle with looking at it now…

While Mako and Sailfish are not identical, and not completely joined at the hip, I’m trying to learn a lesson here and will look at both.

Mako Mining

Mako Mining has three principal assets:

It has 188 square kilometres in Nicaragua, which includes the San Albino deposit/mill.

Despite only really mining the San Albino and Las Conchitas deposits, Mako produced almost 40,000 ounces of gold in 2024, earned $0.25 (USD, all prices will be in USD except for share prices), and had a return on (end of year) equity of ~27%. Keep in mind that I’ll be using San Albino and Nicaragua more or less interchangeably. The gold isn’t necessarily getting mined from San Albino, but that’s the only mill, so I figure it’s sufficient shorthand to say San Albino.

This year it acquired the Moss Mine in Arizona out of bankruptcy. Moss is a producing gold mine that I will expand on, but for now I’ll say it’s a reasonably large operation.

In 2024 Mako acquired Goldsource, the main asset of which was the Eagle Mountain mine in Guyana.

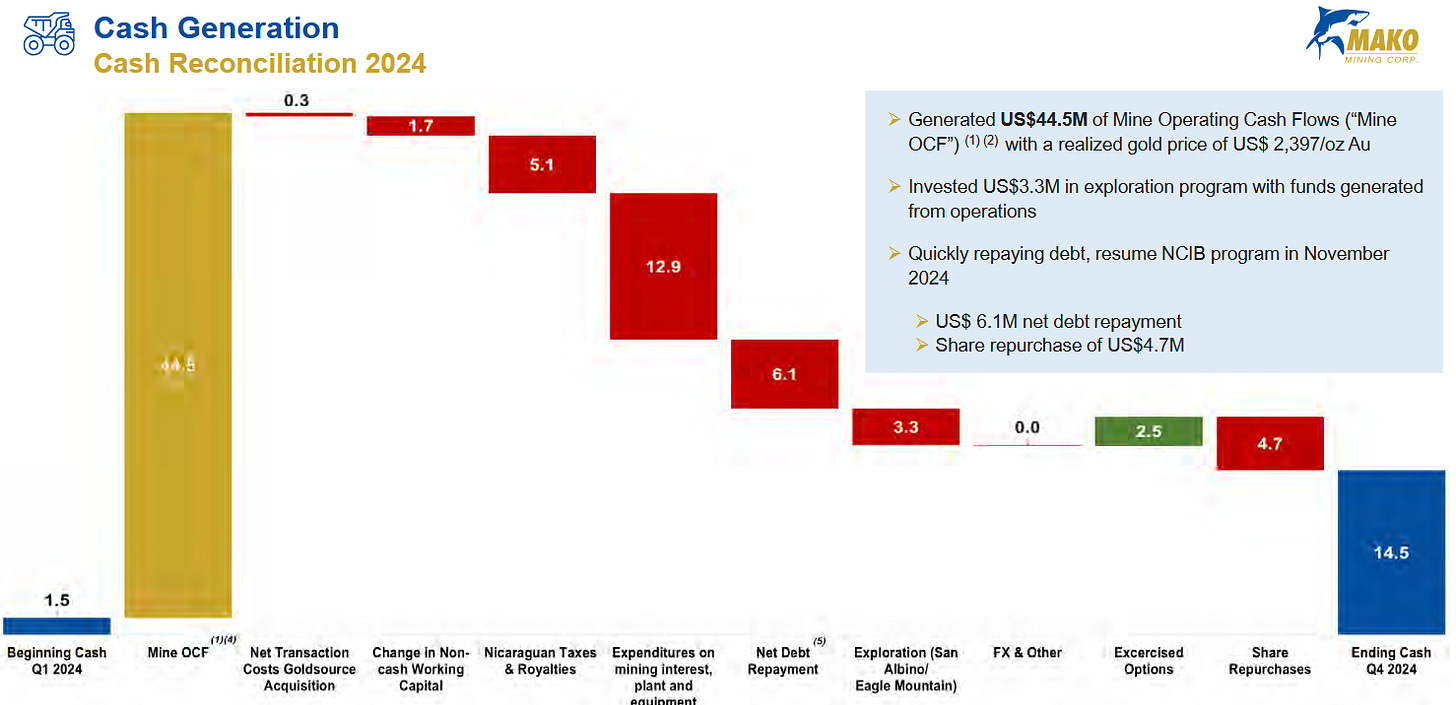

The San Albino mine is flowing a lot of cash:

During 2024, San Albino produced $44.5 million of operating cash flow, and that was with selling gold at ~$2,400 per ounce, almost $1,000 less than gold sells for today. In the first quarter of 2025, revenue was up to $31 million vs $19.2 million in the same quarter last year, with gold sales only ~15% higher (10,800 oz vs 9,300 oz). That increase in ounces and revenue came with very little production from the Moss Mine, and with an average sale price of still less than $3,000. Cash flow will only be higher going forward, but Mako’s valuation with just San Albino contributing is compelling.

In 2024, Mako’s all-in sustaining cost (AISC) was $1,371/oz. If we can assume 40,000 oz of production and $1,500/oz AISC, San Albino would produce ~$60 million of cash flow at an average gold price of $3,000 (marginally higher than Q1 but ~10% lower than recent prices) or $40 million at $2,500 gold (much lower than today, but higher than last year). Mako has nominal debt and a cash balance, so the enterprise value and market cap are both around $250 million USD.

That $40-$60 million of mine operating cash flow probably leads to $25-$45 million of free cash flow. What does the company do with the free cash flow?

As you can see above, Mako has chosen to spend some cash on buybacks. It has paid down debt. And we know that it has acquired two mines in the last year (one bought with equity though).

Mako might chose to do more acquisitions, and hopefully it does given how accretive the two deals look, but there are plenty of opportunities to invest internally.

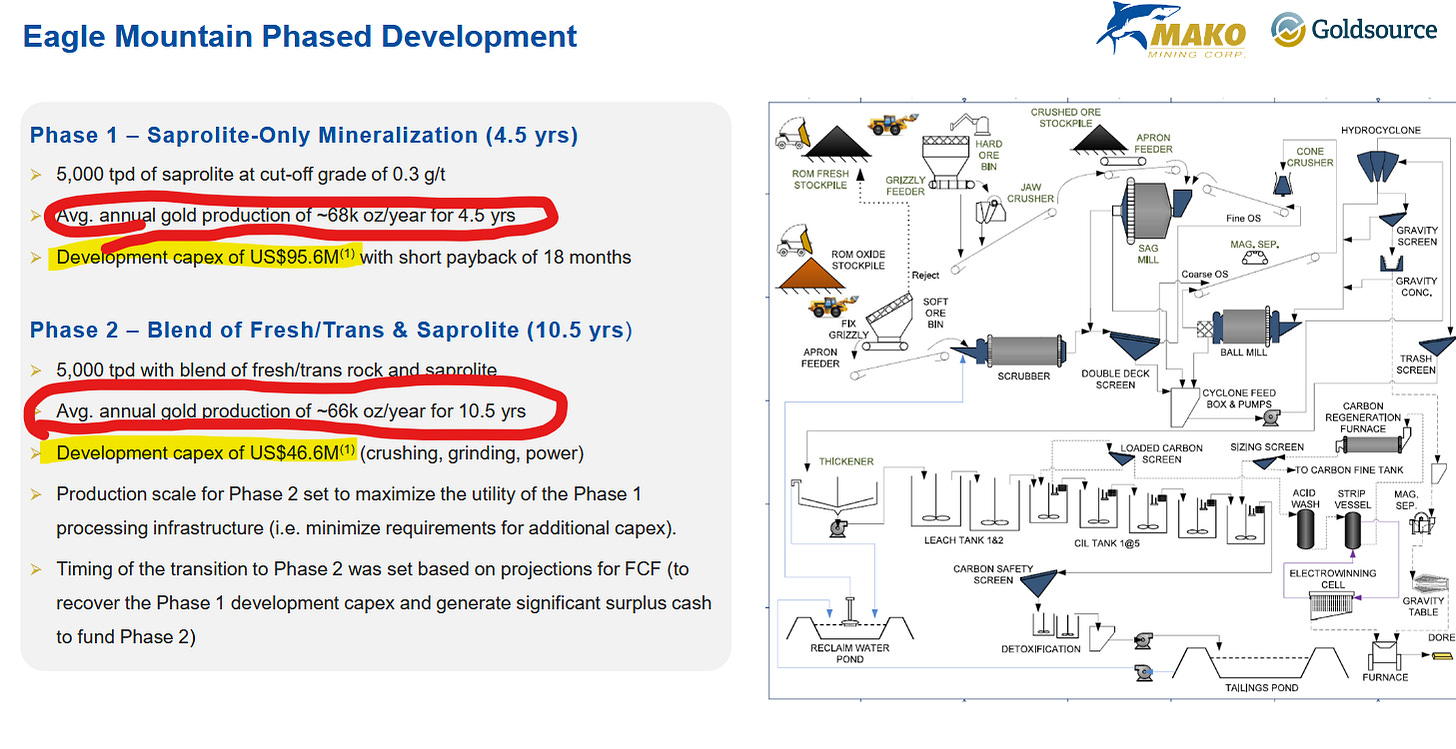

Eagle Mountain is the big one.

Mako has the opportunity to invest ~$140 million into Eagle Mountain, which means the company can reinvest essentially all of its cash flows into a fully owned, low cost gold mine.

Moss will also require some investment to bring it up to speed again and optimize performance, though this really shouldn’t take much cash.

In addition to those two projects, as mentioned Mako owns 188 square kilometres in Nicaragua, with just a small portion of that in production or even explored. And there should be opportunities to drill at Moss and find more gold to expand the resource. It’s riskier to spend money drilling holes searching for gold than spending money to mine gold you already know is there, but there’s reason to believe that Mako owns a lot more gold than it is getting credit for that it can drill for.

But I’d like to return to the Moss acquisition while we are talking about capital allocation. It was this acquisition that finally made me see the light.

Mako purchased the Moss mine out of bankruptcy. Read this paragraph:

The aggregate purchase price for the acquisition was US$6.49 million, paid in cash, reflecting Wexford’s approximate acquisition and closing costs of US$4.9 million plus US$1.59 million of equity contributions made by Wexford to cover initial operational costs at the beginning of January 2025. This equates to the approximate cost basis of EGA’s investment in GVC. Since December 31st, 2024, a total of 1,593 ounces of gold and 11,023 ounces of silver have been produced for a value of approximately US$4.8 million, generating net cash of approximately US$3.0 million. Furthermore, Trisura Guarantee Insurance Company has agreed to release approximately US$1.5 million of the US$3.0 million held as collateral for various environmental bonds held at the Moss Mine. The two aforementioned cash inflows have effectively reduced Mako’s net cash acquisition cost to approximately US$2.0 million, which is a small fraction of Mako’s current monthly cash flow.

The Moss mine has been producing something like 30,000 ounces of gold a year, and Mako paid just $2 million to purchase it. Now Mako is going to have to spend money to increase production and reduce costs - the previous owner went bankrupt which should give you an idea of its costs at the mine - but it looks like an absurdly cheap acquisition.

To give you just a hint, in the first quarter of 2024, Elevation Gold, the previous owner of Moss, reported an AISC of $2,437. A mine with that high of costs is only feasible at very high gold prices… like we have today. Mako’s AISC will not be that high, I can almost guarantee that, but let’s imagine that Mako spends $10 million to refurbish Moss (I think that’s a high estimate), and produces 30,000 ounces at that same $2,437 AISC. Well at $3,000 gold, that would still be almost $17 million of earnings in the first year of production vs $12 million of acquisition and start up costs. If you consider that gold is trading higher than $3,000, that Mako will be able to lower costs and may be able to increase production, well, the numbers start to look silly.

Mako was able to acquire Moss because of its relationship with Wexford Capital, as is noted in the quoted paragraph above. Wexford owns 48% of Mako, and has been the controlling shareholder since 2018 when Mako was created. Wexford has been a benevolent overlord, and has loaned money to Mako with flexible terms and has participated in equity offerings (making it easier for Mako to raise money). I saw those things and could understand how Mako was benefiting, but the benefit was relatively mild, and I also thought Wexford was benefiting.

This Moss deal is the best example of how the relationship benefits Mako. Wexford are good investors, and made a great deal to buy Moss, and then sold the mine to Mako at Wexford’s cost.

When reading about Mako, the Wexford relationship was always held up as very positive. This is the most positive thing I’ve seen yet, and it’s a perfect example of how I’d want Wexford to help Mako. I’ve seen Mako mentioned as “Wexford’s gold vehicle”, but this acquisition really proves it. If Mako is able to leverage Wexford by sourcing deals (as it did with Moss) or by facilitating deals (Wexford loaned Goldsource money while it was being acquired by Mako) or whatever, I have a lot more faith in Mako’s ability to capitalize on M&A during what looks like an exciting M&A market.

I don’t know the market that well (“well then shut up idiot!”), so I’m not familiar with many gold miners. I wouldn’t feel comfortable picking the proper comparable companies to come up with what multiple would make sense based on that. So much of the multiple would have to do with the jurisdictions they operate in, the current production, the known mineral resource estimate, and how much more gold the market expects the companies to find - I could find some imperfect comps, but I’d rather not.

What we can do is look at Mako as it is today, or rather as it will be in early 2026.

The company will still in all likelihood be producing 40,000 ounces of gold annually in Nicaragua, with an AISC of $1,500 or less, good for $60 million of cash flow at $3,000 gold (making every dollar above that gravy).

Moss could easily be producing 40,000 ounces, as it has done in the past, but let’s say it is producing just 30,000 ounces. While the last quarter we have data for had the AISC at $2,437, costs at the Moss Mine were not always so high.

The average cost during this period is $2,166. Excluding the large outlier, we can see costs gradually increasing. Mako has already gotten rid of a few royalties on the property during the bankruptcy process, which are costs that have already been eliminated. Whether another 4% of royalties are eliminated is being decided on now, which would further reduce costs.

Mako CEO Akiba Leisman is very active on Twitter - which can be a red flag but from what I’ve seen Akiba is more candid than promotional - and has discussed the costs at Moss a bit:

My point here was to “model” Moss. If Moss production stays around 30,000 ounces and costs don’t drop at all, Mako will be earning ~$17 million from the mine at $3,000 gold. If costs drop to the $2,166 average of the past ~4 years, earnings would be $25 million. The upside that comes from (the already) higher gold prices, higher production, or lower costs, can all be ignored for now. All of those seem very likely, especially the lower costs.

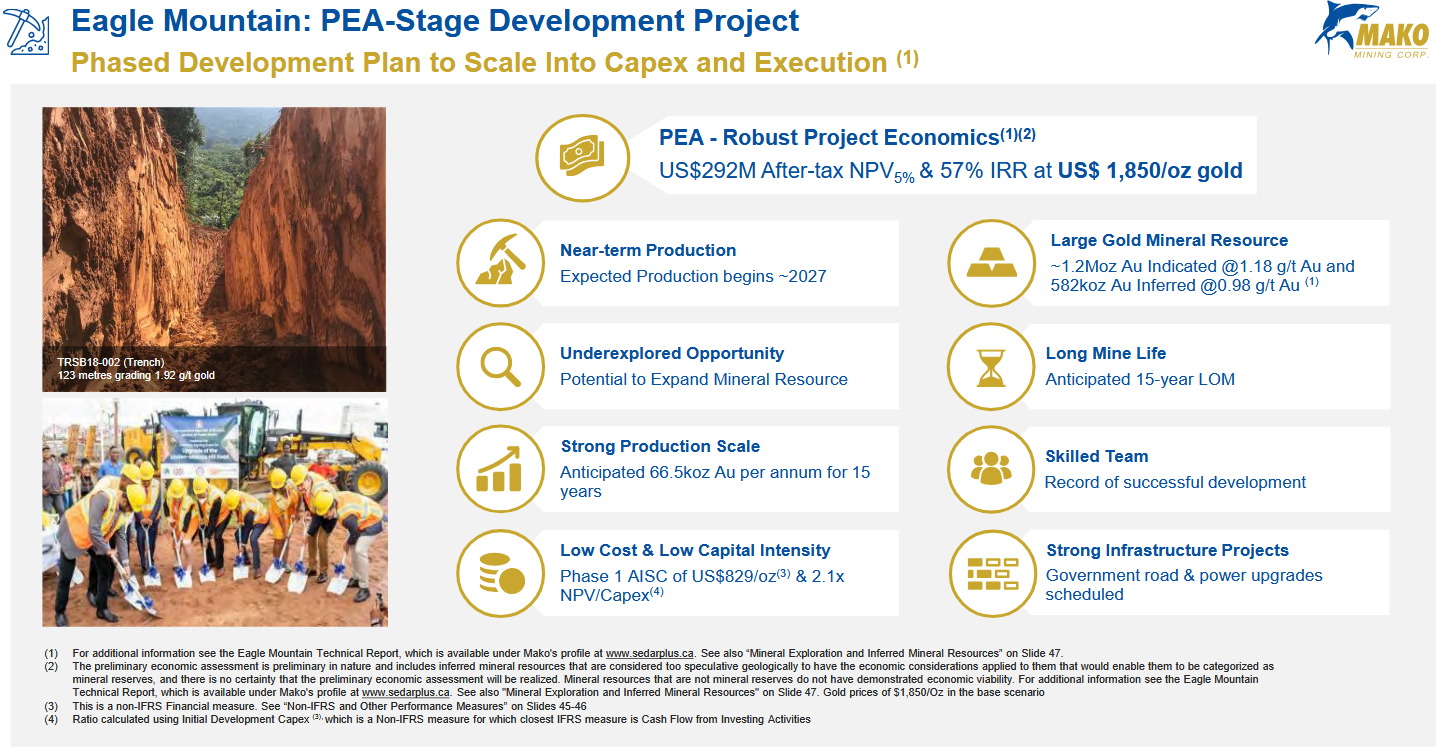

At some point in 2026, Mako will report a run rate of earnings/cash flow of $75 million or so (after ~$10 million of costs/taxes not captured in AISC). That $75 million should be fairly steady, maintained with relatively low capital expenditures to drill in Nicaragua and at Moss. Meanwhile, Eagle Mountain will be 1-2 years away from producing 66,000 ounces per year of gold at $1,200 AISC.

The market, if it looks forward enough, should be able to see Mako as a 140,000 ounce producer in a year or two, with cash flow of something like $200 million.

I don’t know what multiple the market would give that company. Do junior miners trade at ~5x cash flow (in this sense I think my cash flow numbers are somewhere between operating cash flow and free cash flow)? At 5x the 2026 run rate, which wouldn’t make sense when cash flow is so close to exploding higher, Mako would be worth ~$6.50 Canadian. In fact, Mako right now is trading at less than 5x the cash flows from just San Albino.

My conservative estimates of multiple, costs, and possibly the price of gold, could lead to much more upside.

I mentioned above how I am uncomfortable with forecasting gold prices, and even using prices 10+% below the current spot price makes me a bit uneasy. Using $2,500 gold makes the numbers much less compelling, but Mako would still earn $35 million to $40 million of cash flow before starting up Eagle Mountain. That’s still like a 7x multiple today. If Eagle Mountain starts up at $2,500 gold, cash flow becomes ~$110 million, and the current $270 million market cap doesn’t make any sense at all.

I’ll add one more valuation data point to consider. I’ll show you this slide again in case you.

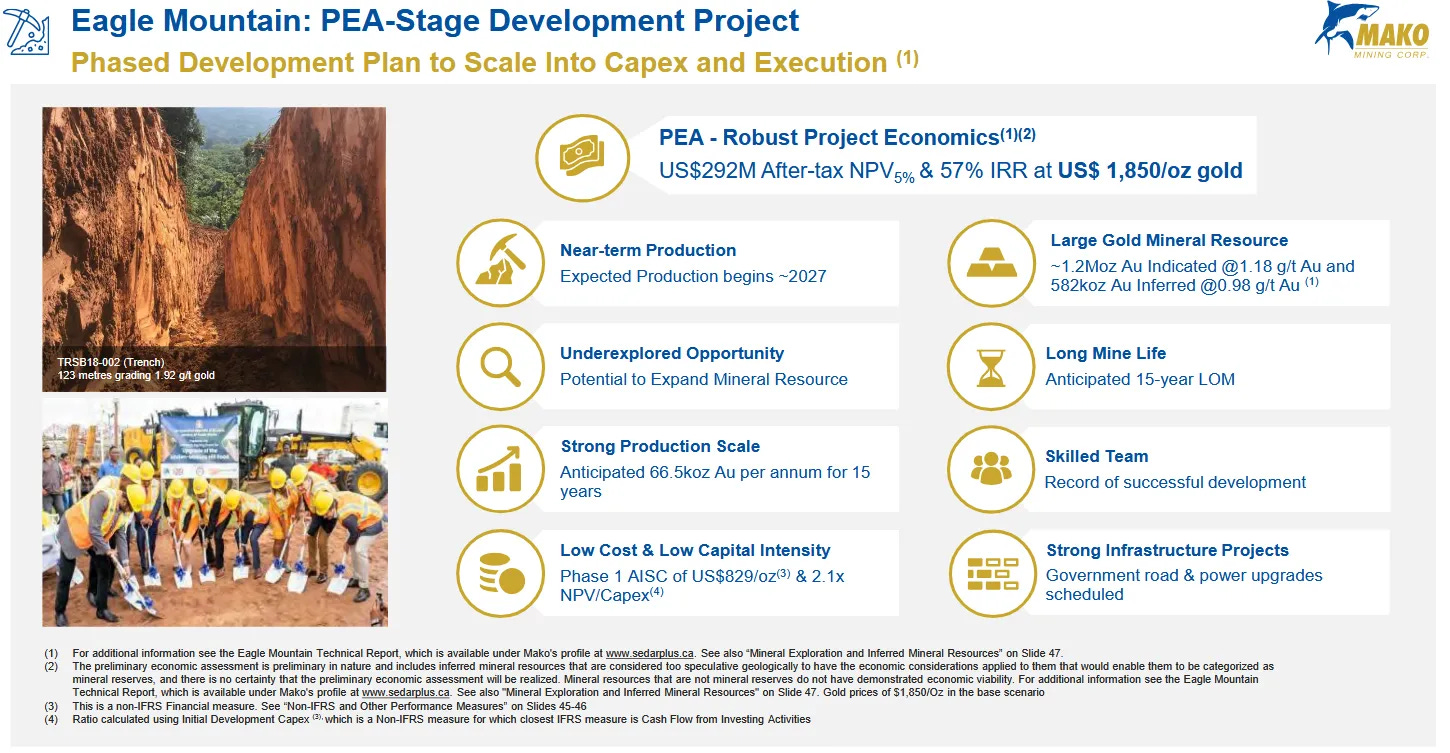

It says the net present value (NPV) of Eagle Mountain is $292 million. Mako’s current market cap is $270 million. The 5% discount rate used is low, but seems to be standard for the industry. We can call into question the discount rate, but then we’d also have to call into question the $1,850 price of gold that NPV uses.

Goldsource produced that preliminary economic assessment (PEA) in January 2024, and when it was doing the sensitivity analysis, couldn’t even fathom that gold would be $3,300/oz.

Even so, we can see that increasing the discount rate does not nullify the impact of higher gold prices. I’m sure I could calculate the NPV using $3,000 gold and the 10% or 12% discount rate I’d rather use. Given where Mako trades now, and the numbers in the table already, I can just know that the NPV is much higher than the current share price.

Between the valuation of Mako, its high return opportunity to reinvest cash flows, and the excellent capital allocation I’ve seen and can be confident of going forward, I think Mako is a fantastic opportunity almost regardless of the gold price. I can invest knowing Mako is still cheap if gold drops ~25%, and I can participate in either further upside in gold or if it remains flat at these high prices.

Now that we’ve looked at Mako, we can look at Sailfish, which has the same controlling shareholder (Wexford), the CEO of Mako is the chairman of Sailfish, and they both “share” the Nicaragua assets.

Sailfish Royalty

Sailfish is slightly harder to evaluate now than when I did it four years ago, but only slightly.

The main asset is San Albino, which I didn’t even bother to evaluate before.

Sailfish has a 3% NSR on San Albino (it’s actually a stream equivalent to a 3% royalty, but I digress) and a 2% royalty on the rest of the Nicaragua lands. Sailfish has also paid $7 million to receive all the silver that Mako produces in Nicaragua.

Gavilanes, or what I called Swordfish in my previous write-up, is an exploration silver property that Sailfish just sold in late 2024. Much less than the $8 million I assumed above, Sailfish received ~$550,000 up front (mostly in Advance Metal shares), as well as PSUs were another ~$1 million if Advance is able to come up with another ~40 million ounces measured & indicated silver in the next five years. Regardless of what I thought it was worth before, Sailfish currently has a 2% NSR royalty on Gavilanes, along with the possibility of receiving some future performance payments if things work out. I don’t think this is worth a whole lot.

Sailfish has two royalties on other projects in Mexico that I don’t think amount to much value.

Finally, Sailfish still has the Spring Valley and Moonlight royalties. While I was way over on my estimate of Gavilanes, I was way under on my estimate of Spring Valley. Or more accurately I think the value is much higher now than it was in 2021.

Let’s start with San Albino/Nicaragua. In 2024 Mako produced ~40,000 ounces of gold and another ~40,000 ounces of silver. San Albino itself is mostly mined out, unless Mako begins mining underground (which is the plan at some point), so while some gold is coming from San Albino and will in the future, it’s easiest for me to assume that Sailfish will just get a 2% royalty on the 40,000 ounces of production. 2% on $3,000 gold and a high estimate of smelting costs leads to $2.16 million of royalty revenue, and the 40,000 ounces of silver will be worth another $1.2 million (assuming $30 silver).

That $3.3 million isn’t much, but it does more or less cover the overhead and a decent chunk of the dividend or share buybacks.

The real story is Spring Valley.

Osisko Royalties bought royalties at Spring Valley for $26 million in 2021 and back then that was obviously the best value to put on Sailfish’s Spring Valley royalty. That was what a sophisticated buyer was happy to pay. In 2021 though, there was very little news out of Waterton (the owner) or Spring Valley. We didn’t know what was going on with it, didn’t know if it would ever get mined, and so on.

Now we have a very recent feasibility study showing a huge net present value and quick payback even if gold was just $2,400, and it shows 300,000 ounces per year of production. The environmental impact statement is expected to be released by July 11th, and a record of decision is expected in August. If everything goes according to plan, construction is expected to start shortly afterwards and production to start in 2028:

What is 300,000 ounces of gold a year worth to Sailfish? It’s hard to say exactly given the royalties Sailfish have are different rates in different areas, and we can’t know where the gold is going to come from.

If somehow all of the gold produced came from the 0.5% areas, royalties would be ~$4 million. If it were all from the 3% areas, they’d be ~$25 million. Split the difference and assume a blended rate of 2%, and royalties would be ~$16 million. I think that’s low since I use very high smelter costs, production is higher in the early years making those cash flows more valuable and 2% seems too low for the average royalty, but that conservative estimate still shows how valuable Spring Valley is.

If Sailfish is earning ~$15 million in 2028-2029 (all G&A is covered by Nicaragua remember), and it still has exploration/development upside (we haven’t discussed Moonlight, which is right beside Spring Valley), what might it trade for?

In this case, I am more familiar with royalty companies than miners, and I happen to have a recent comparative valuation chart, so I’m a bit more comfortable slapping a multiple on here:

This suggests that for royalty companies, 20x EV/EBITDA is a somewhat common multiple, which would make Sailfish worth $300 million in 2028 or 2029, or be ~$5.50 per share (compared to ~$110 million and $2 now). Discount that back to today and you get a fair value of $3-$3.50.

Management of Sailfish have also brought up a recent royalty purchase as a comparable for Spring Valley. In April, Triple Flag Precious Metals acquired Orogen Royalties and its 1% NSR Silicon gold mine royalty. As part of the acquisition, a new spinoff company was made to hold all of the non-Silicon assets, meaning the acquisition is a pure valuation of that royalty.

As you can see, the mines aren’t identical, but they share similarities. They’re both large Nevada mines. While Silicon has 12 million ounces and is expected to produce 600 million ounces annually, the mine isn’t even planned to start until 2032 (and who knows what could happen between now and then), and Triple Flag only purchased a 1% NSR royalty. Spring Valley should start producing much earlier, and even though production will be half of Silicon, because Sailfish has a greater than 1% royalty, Sailfish will be earning just as much or more (most likely more) from its royalty as Triple Flag will. I’m not sure exactly how the valuations of the two compare, but I can see why Sailfish would consider them comparable, and I think there’s good reason to think that the Spring Valley royalty is worth more. Certainly if there’s a positive decision in August and construction starts shortly after that, the cash flows being so near in the future will weigh the comparison in Spring Valley’s favour.

Again, Sailfish’s market cap is $110 million. Would an acquirer pay $248 million to purchase the Spring Valley royalty? Maybe, maybe not. Would an acquirer pay much more than $110 million? Definitely.

And what about Moonlight?

I’m not going to pretend to value this. Terraco Gold, which Sailfish acquired in 2019, did a little bit of drilling at Moonlight in 2010 and 2011, but there weren’t enough results to worry about. Because Waterton is a private company, we have no idea if more drilling has been done at Moonlight, or what the results may have been. For now, Moonlight will just remain as unaccounted for upside.

Conclusion

There are definitely risks to these companies; I dont’t want to act like there isn’t.

A lot of the value of both companies is in Nicaragua, which could give some people pause, though both companies are now diversified. If something happened to Mako’s Nicaragua mines, Sailfish is probably worth more than its market cap based on Spring Valley alone, and Mako’s operations in Arizona and Guyana are worth a lot as well.

Wexford Capital controls both companies via its 48% ownership of Mako and 61% ownership of Sailfish. I think Wexford is a net positive for both companies, with the best evidence being the Moss acquisition, but it’s possible that Wexford could do something in its own best interests vs minority holders. Wexford’s investment in Mako is significantly larger than its investment in Sailfish, so there is a risk that related party transactions favour Mako, though Sailfish’s board seems independent enough to protect the company (including the aforementioned Brown aka Asheef Lalani).

Gold prices of course…

Both companies are very illiquid, which isn’t a problem for a peasant like me, but someone trying to build a large position might have problems building the position and/or getting out of it.

If there are problems at Moss (costs remaining high) or Eagle Mountain (any of the myriad problems that can happen while constructing a mine), Mako would be hurt. Similarly, Sailfish is very much reliant on Spring Valley progressing, and while everything looks good right now, anything can happen.

I’m comfortable with those risks on their own, because I have considered their chances and thought them worth the possible reward. But I have also ignored so much upside that I think it’s just as likely that I am positively surprised by results.

Mako should be able to reduce costs at Moss much more than just to the average of the previous operator over the last several years. It’s also quite possible that Mako can increase production at Moss or San Albino.

And of course the highest gold price I used in any of my estimates was $3,000, and both stocks are still attractive if gold falls to $2,500. But gold is over $3,300, and has gotten close to $3,500 recently. It’s at least possible gold could go even higher, which of course is great for these companies.

I have been dumb and not looked at these companies until now, when I had strong suspicions were cheap. It hurts me to know that if I had looked at either of these companies, I probably would have come to similar conclusions as I have now (both are too cheap) but would have gotten to buy the stocks at $3.00 and $1.50 or somewhere in those neighbourhoods, instead of almost $5 and $2 now. But seeing the Moss Mine acquisition really solidified my impression of management and Wexford, so waiting for that wasn’t the worst thing. And while Triple Flag’s Silicon royalty acquisition is not a perfect comparable for Spring Valley, I do think it justifies a value considerably higher than Sailfish’s market cap.

I don’t know exactly what these companies are worth. I wrote above how $7.50 for Mako and $3.50 for Sailfish might make sense, but those were very rough estimates, based on conservative valuation metrics that I’m only somewhat committed to. What I do know is that these companies are worth more than they can be purchased for in the open market, and that I have a high regard for the management team’s and Wexford. If I’m going to have exposure to gold, which I have decided far too late that I should, I want to get it through owning these companies. They are undervalued and well managed, with Mako on the verge of tripling production and Sailfish owning a royalty worth more than its market cap on a huge mine approaching approval and construction.

enjoyed reading!!

Thanks for the comprehensive write up. Thoroughly enjoy reading this sort of analysis as while all the Information is out there - most investors will pass on it if it requires a decent amount of analyst /investigation. Keep up the great work 👍